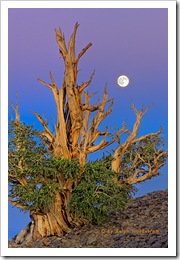

A few weeks ago I posed a photographic challenge. What decisions would you make to capture the Bristlecone Moon image? Here’s the photograph again.

This shot poses some interesting challenges and here’s a link to the first post that spells out the situation in case you missed it.

Photographic Challenge – the Situation

The planning for this photograph actually began several months before. I had the idea of photographing a bristlecone pine with the full moon as it rose behind it through the earth shadow. The earth shadow is that ribbon of color that is projected in the sky above the horizon directly opposite the rising or, in this case, setting sun. So the first step was to select a full moon weekend, contact my buddy, Eric Winter and head up to Grand View campground in the White Mountains. We arrived three days before the full moon to scout the area and find a tree that had everything I was looking for – an open view to the east that looked down on the Great Basin below. I also new I needed to have enough room to back away from the tree so I could use a telephoto and thus increase the relative size of the moon.

There are only two named bristlecone groves in the Whites – Schulman Grove where the oldest tree is found (4,700 years old) and the remote Patriarch Grove. The Schulman Grove is at the end of the paved road and just a few miles from Grand View campground. The Patriarch Grove is another 8 miles down a dirt road and when the rangers say it’s a 45 minute drive you’d better believe them cause it is.

The first day we scouted the Patriarch Grove but unfortunately, it is in a broad depression that has a large hill to the east. There weren’t any trees that had what I was looking for. The next day we killed some time in Bishop and dropped into Vern Clevenger’s gallery. Vern and I chatted and I told him what I had in mind. He advised me to get the shot one or two nights before the full moon, not the night of the full moon. It turned out to be a critical piece of advice that I needed.

So back up to the Whites and back out the dirt road in a search for THE tree. We scouted a couple of places but none worked out. We climbed back into the truck and continued down the road. “What about that tree?” Eric asked as we drove by. It was perfect. Throwing the truck into reverse, we backed up and parked off to the side of the road.

The tree had a clear view of the eastern horizon. There was a large hill to the west but all that meant was that the tree would be dropping into a shadow long before the sun dipped below the horizon. There was enough space to use my 70-200 lens and back up far enough to fill the frame with the tree.

I had printed the moon charts from the internet so I new the precise time and azimuth of the moonrise and was able to figure out where I wanted to position myself.

I started working with compositions well before the moon was due and decided to crop off the ends of the branches because I liked the proportion better. Then I sat on Mother Earth and quietly waited. The shadow from the hill to the west crept across the road toward the tree and finally swallowed it. I sat, looking to the east, waiting for the moon to rotate into view. Sitting up high on the side of the White Mountains I got a strong sense of the earth turning on its axis, rotating until the moon appeared above the horizon. One moment it wasn’t there and the next it was. It was time to go to work.

The moonrise was playing out just like I had hoped. This is when I get nervous. “Slow down, don’t make a mistake,” I kept telling myself. Depth of field: f/16. Shutter speed: 1.2 sec at ISO 100. Too slow. Bump the ISO to 200. I heard Ansel Adams speak years ago at Pasadena City College. He told the story of taking “Moonrise over Hernandez.” He didn’t have time to take out his spot meter and do his usual zone thing. So he exposed for the moon. He knew it was in full sunlight and he knew what its luminance was without having to measure it. So he put the moon in Zone VII and fired away. I was thinking of him when I realized that I needed to shoot HDR if I wanted the moon to be more than a blank white disk, if I wanted to catch the man in the moon.

So I turned on the camera’s Highlight Tone Priority function to gain a little extra dynamic range, kept the ISO at 200 and bracketed the exposure by one stop. The focal length was 185 mm and the total elapsed time for the three exposures was about 2 1/2 seconds. At 185 mm you have 3.2 seconds to get your shot off without the moon (or stars) moving perceptibly. (There’s a formula for calculating that. It’s 600/focal length in mm. It’s a handy formula to know. See Ten Tips for Exciting Nighttime Photography.)

So that’s pretty much the whole story. There are other ways go solve this challenge. Carefully exposing the moon to fall at the right end of the histogram without highlight clipping would result in a capture in which both shadows and highlights could be recovered in Lightroom or Photoshop. A graduated neutral density filter is problematic because it would cover part of the tree. So HDR works well in this situation because you get a good exposure on both the moon and the tree.

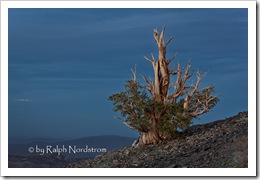

I’ve returned to this tree several times since September of 2008 when this photograph was taken. It’s one of the stops on our Eastern Sierra workshop. Each time I return it has a different feel to it, a different mood. Here’s what it said to me this year.

It’s a remarkable tree and I plan to keep on coming back.

Join me on an upcoming workshop.

To see more of my photographs click here.

(903)