From time to time the term ‘Gestalt’ has come up in articles and classes on composition. I never quite grasped the concept. I thought Gestalt is an approach some psychologists use in their counseling. And to make matters even more confusing, the origin of the term didn’t help. It comes from the German word that means ‘shape.’ It just wasn’t sinking in. Until recently….

The concept started to make sense as I was preparing the Mastering Landscape Photography class for the Joshua Tree National Park Desert Institute here in California. In this course I take a deep dive into light and composition. I’ve been studying the ‘rules’ of composition for many years now and the authors tend to make broad generalizations on the effect they have on the viewers. More recently I studied the impact colors have, not from the perspective of visual arts but rather from the studies performed by researchers in psychology. Through their studies, the researchers found that the colors they studied, generally prime colors, can have either a positive or negative effect on their subjects. And the effect depended on many factors but based on these factors they were consistent. That got me thinking.

Every source that I checked on diagonal lines made the same assertion. They create a sense of motion and energy in the viewer. That’s pretty much universally true. And where there’s motion, there is a direction. The generally accepted rule is that diagonal lines that go from the upper left to the lower right have a downward direction; that is, they are descending. The opposite is true for lines that go from the lower left to the upper right. They are ascending.

In these examples where the lines are isolated, I think you would agree with me that this is true. This is a reliable response in virtually everyone.

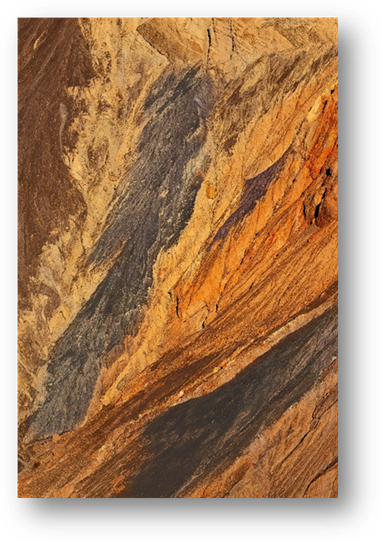

But incorporate diagonal lines within the context of an image and these rules become ambiguous. For example, take this image of a section of the wall at the Ubehebe Crater in Death Valley National Park, a crater a half a mile wide and 600 feet deep that was created by an explosion of steam of all things.

This vignette has very strong diagonal lines going from lower left to upper right. And yet many people (but not all that I’ve asked) perceive these as descending diagonal lines. This downward energy is created from many other visual clues that direct the energy downward. The two dark areas frame the central area forcing it to converge toward the bottom, pointing in that direction. The influence of these three elements is stronger than the ascending diagonal line rule.

Therefore, the effect of the image arises from the interaction of all the elements within the image. And these interactions can redefine the roles individual elements play. Taken as a whole, this image is a contradiction to the generally accept view that diagonal lines from lower left to upper right have an upward motion and energy. Not always.

It’s worth mentioning that not everyone sees the energy as moving downward in this image. It’s very interesting to study what our brains do when they receive these images from the optic nerves. Much of the processing the brain does produces near-universal result. But the experiences and memories of the individual who is viewing the image can sometimes become the more dominant factor in the response. Hence, we get our own unique individuality and potential variations in the responses from one person to another.

Let’s look at an example where the ‘rules’ apply. This next image is from 20 Mule Team Canyon, again in Death Valley. In the bottom of the image there is a streambed t that moves from upper left to lower right. Take a look.

It appears to be moving downhill from left to right. Not only does the ‘rule’ apply but we also know from our experiences that water flows downhill which supports the impression.

An exception to the descending rule is found in Death Valley’s Aguereberry Point. This rock outcrop is the iconic representation of this amazing viewpoint, 6000+ feet above the valley below.

Although the strong diagonal lines go from upper left to lower right, the rock is seen as bursting out of the ground with great energy. Our brains subconsciously see that both rocks are pointed on the end which reinforces the direction of travel, overriding the ‘rule’ in this case.

What is it that causes some diagonal lines to follow the ‘rule’ and others to violate it? It’s the context within which the diagonal lines are found. Other elements may counteract the diagonal lines and carry a greater influence. Add to that the experiences and memories of the viewer and the ‘rule’ can be even more effectively overruled. It is the image in its entirety that determines its mood. And that’s gestalt.

This can be summarized in a common refrain; “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” It is all the elements of an image, the subject, composition, light, sharpness, tonality– that come together to create the expressiveness of the image, the impression it creates, the message that it carries.

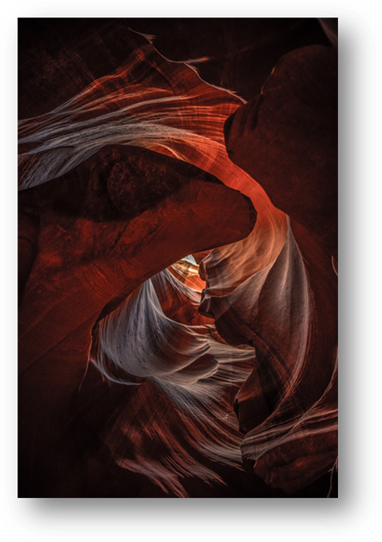

With this in mind, take a look at this image from Antelope Canyon near Page, Arizona.

Most photography books and articles you read about the color red will extol its vibrant, inviting, attention grabbing, exhilarating qualities. They suggest that red has a bright, uplifting effect on most people. But this image is a clear exception. With all the swirling turmoil, the red takes on a hellish glow as if the rocks were red hot.

The message I want to leave with you is not to ignore the ‘rules’ of composition. On the contrary, they form the foundation upon which we build our images. It’s important to be aware of lines and thirds and layers and the many compositional elements at our disposal and to use them effectively. But there will be times when Mother Nature herself will present us with situations where the rules fall short and these times can also result in powerful images, as long as they have gestalt, as long as all of the elements work together.

How can this knowledge of the role of gestalt affect your photography? Are there precise, analytical criteria to determine if an image is infused with gestalt? Is there a checklist? No. Gestalt doesn’t work that way because it involves a holistic view of the image, a view that does not get bogged down in details but sees it in its entirety. Granted, there is a period in the process of composing an image where you must pay very close attention to the details. But in the end, before you press the shutter button it’s beneficial to stand back and look at the whole image on your camera’s monitor and ask yourself, ‘How does it feel?’ If it feels right, then you have a successful image.

Join me for an exciting and productive photography. Check out Ralph Nordstrom Photography Workshops.

(215)