She deferred her career that would bring her international fame until her three children were adolescents. She entered the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York at the age of 37 to study portrait painting. At the age of 45 she opened her own portrait studios and in just three years she was considered by some to be the greatest photographer in the United States. Here is her remarkable story.

The Early Years

Gertrude Stanton was born on May 18, 1852 in Fort Des Moines, Iowa, later to be known simply as Des Moines. Her parents were John W. Stanton and Muncy Boone Stanton.

n 1858 the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush erupted and in 1859, Gertrude’s father moved to the Colorado Rocky Mountains. He ventured by himself to Eureka Gulch to try his luck. He realized that hunting for gold was a hit-and-miss proposition but providing lumber for the building boom that would surely develop was a sure thing. He built a sawmill and was right. A year later, John brought his family west to live with him. The town of Eureka Gulch was renamed Golden and became the capital of the Colorado Territory. John was well liked and was elected Golden’s first mayor. Many of Gertrude’s playmates in Golden were American Indians and her contact with them resulted in a deep regard for them and would be the heart of some of the most beautiful and moving portraits.

In 1864 the effects of the Civil War were felt in the Colorado Territory and John thought that it had become too dangerous for his family, so they moved back to the East Coast and settled in Brooklyn, New York. There John worked in mineralogy and Muncy rented out rooms in their home to boarders to earn a little extra money. Gertrude was already showing an interest in art, even at an early age. She removed some of their paintings from the wall, placed them flat on the floor and knelt next to them, pouring over them, examining every detail with the intent of understanding how she could to that.

In 1868, Gertrude moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania to live with her maternal grandmother. The reason for the move was so she could enroll in the Moravian Seminary for Women, the first women-only school and an institution of high repute. While living in Pennsylvania she would make periodic trips back to Brooklyn to visit her family.

On one of those trips, she met a gentleman who happened to be boarding there – Eduard Käsebier. He was a handsome enough fellow, who came from a German aristocratic family and had a pleasant disposition. Rebounding from a failed relationship, Gertrude married Eduard in 1874. She was 22. Gertrude’s mother was delighted with the match. Eduard had built a successful business in New York importing shellac. She saw him as a perfect match for her daughter. In the first six years of their marriage, they had three children – Frederick William born in 1875, Gertrude Elizabeth born in 1878 and Hermine Mathilde born in 1880.

Even as a young girl, Gertrude was independent and strong willed. She also had a natural talent for art. These qualities gave her the drive and the ability that would help carry her to the heights of achievement that she would later enjoy. But Gertrude and Eduard were people with markedly different personalities and needs, and neither could fulfill the other’s needs. The marriage, instead of being a success, deteriorated into irreconcilable differences and even hostility. The Victorian social norms of the day precluded even the thought of a divorce, but their relationship became so bitter that they ultimately separated. She was quite explicit in her feelings about marriage when she said, “If my husband has gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible…Nothing was ever good enough for him.” Gertrude took the children and moved to a farm in New Durham, New Jersey for a healthier place to raise her children. Eduard continued to support them. He couldn’t have been all bad.

Käsebier was a devoted mother but she still found time to pursue her passion for painting. “After my babies came, I was determined to learn to use the brush. I wanted to hold their lovely little faces in some way that should be also my expression, so I went to an art school; two or three of them, in fact. But art is long, and childhood is fleeting, I soon discovered, and the children were losing their baby faces before I learned to paint portraits, so I chose a quicker medium.”

The Middle Years

In 1889, when her children were approaching adolescence, Käsebier enrolled in the prestigious Pratt Institute to formally study portrait painting. She was 37 when she enrolled and studied there until 1893. Eduard paid for her tuition. At that time the Pratt did not offer instruction in photography. However, many of the students were taking pictures as a hobby, including Käsebier.

1894 was a pivotal year in her life as far as her photography is concerned. First, she won a prize for a photograph of a woman that was printed in the Quarterly Illustrator. When she told her instructors at the Pratt, they criticized her so mercilessly that she was shamed into giving her winnings away. But on a more positive note, she went to Europe where she sought out the German chemist Hermann Wilhelm Vogel whose interest was in the chemistry of photography. From Vogel she learned the chemistry of the development and print processes that she would use throughout her career and that enabled her to be the accomplished Pictorialist photographer she was to become.

But her time in Europe was cut short. The following year she received word that her husband was gravely ill, and she immediately returned to Brooklyn. The doctors gave Eduard a year to live (although he ended up living ten more years). This prompted her to think seriously about starting a portrait photography business, not only to financially support their family but also to fulfill her need to become a portrait photographer.

Before she could do that, however, she had to gain a reputation. So, she apprenticed with the established portrait photographer Samuel H. Livesey whom she knew from the Brooklyn Photographic Club. With Livesey she developed her skills as a portrait photographer, leaned the business and assembled an impressive portfolio of hundreds of photographs.

With a rapidly expanding body of work, she received several photo exhibits in 1895. The Boston Camera Club displayed 150 of her photographs. These same photographs were later displayed at the Pratt Institute. Her style of photography was reminiscent of the Old Master paintings although she denied making any conscious attempt to imitate them.

Also, it is clear that the development and printing techniques she learned from Vogel and that she put into practice in her photography put her squarely in the Pictorialist movement and her keen creative eye placed her in its upper echelon. The aim of this style of photography was to create photographs that looked like paintings. It was a very intensive process that involved painting on negatives and using gum bichromate often of different hues and in several layers in making the prints.

Having acquired a reputation from her exhibits and learned the business side from Livesey in 1897 she opened her studio. She set it up in her apartment to avoid the criticism she was sure to receive from the prevalent Victorian view of women starting a business. A woman working out of the home was OK but out of an office was scandalous. The decor was simple, warm and inviting. She chose this in order to put her subjects in a relaxed, open mood before she put them in front of a camera. Her reputation as a portrait photographer rapidly grew and she was sought out by the upper crust of New York society including actress Evelyn Nesbit, architect Stanford White, author Mark Twain, artist Robert Henri, and photographers F. Holland Day and Edward Steichen.

The Stieglitz Years

In 1898 she extended her association with the elite Pictorialist photographers of the day by introducing herself to Alfred Stieglitz, the most influential photographer of his time. Stieglitz himself embraced Pictorialist techniques and had connections with other Pictorialist photographers such as Clarence H. White and Edward Steichen. Käsebier realized that her association with these well-established photographers could very well accelerate her career. This occurred while Stieglitz was active in the Camera Club of New York.

In that same year, Käsebier attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Seeing the Indians in the show brought back memories of her childhood playmates in Colorado. She sent a letter to William F. Cody, requesting permission to photograph the American Indians in his show in her studio. He agreed and Käsebier started her project of photographing members of the Sioux people, a project that continued for many years. She took an approach that was opposite of Edward Curtis’ who famously photographed the American Indians in their regalia. “I want a real raw Indian for a change…the kind I used to see when I was a child.” She shrived to tell the stories as shown in their faces and, as a result, produced some of her finest work.

Flying Hawk was a warrior who fought in many of the significant battles – The Great Sioux War of 1876, the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Anger seethed inside him and he was unable to hide it. This comes through in his photograph.

1898 was also the year where Käsebier officially joined the ranks of the elite photographers of the nation. The Philadelphia Photographic Salon announced that they were going to create an exhibition of the works of American photographers. They received over 1,200 photographs of which they accepted only 259. And of those that were accepted, ten of them were Käsebier’s. At the age of 46, just three years after her first exhibit, this resounding success established her as one of the finest photographers of the era and definitely put her on a par with the master himself, Alfred Stieglitz.

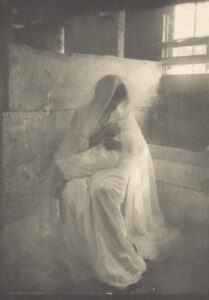

In the following year, her reputation continued to grow. A photograph she created titled “The Manger” sold for $100, the most ever paid for a photograph up to that time and for many years beyond. Stieglitz, who was the editor of the magazine Camera Notes published by the Camera Club of New York, published five of her photographs and declared her to be “beyond dispute, the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day.” And fifteen of her photographs were shown at the Boston Arts and Crafts Exhibition.

In the following years, Käsebier’s impact on photography continued to grow. The Newark (Ohio) Photography Salon recognized her as “the foremost professional photographer in the United States.” Her photographs continued to be featured in numerous magazines. They regularly appeared in the World’s Work: Magazine of the Arts and Public Affairs through 1932. And she participated in the Paris Exposition. Perhaps the most significant recognition of her importance was her election to Britain’s Linked Ring, an exclusive group of photographers. She was the second woman to be elected to the organization.

In 1901 influential art critic Charles H. Chaffin published an article about Käsebier in Everybody’s Art titled “Photography as Fine Art–Mrs. Gertrude Käsebier and the Artistic-Commercial Portrait.” Also, that same year, Chaffin published his landmark book Photography as a Fine Art, in which he devoted an entire chapter to Käsebier. She was even featured in an article in the Ladies’ Home Journal. She spent most of the year in Europe, traveling with Edward Steichen who introduced her to the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Käsebier was able to take numerous portraits of the reclusive artist.

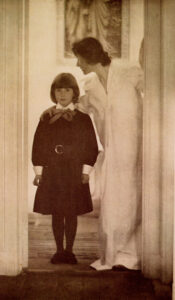

Stieglitz formed the Photo-Secession group in 1902. Its purpose was to promote photography as a legitimate art through the techniques of Pictorialist photography. Käsebier was invited to be one of the founding members. Stieglitz took his experience as editor of the Camera Club of New York’s publication and created a new publication, Camera Work, devoted to the mission of the Photo-Secession group. Stieglitz was so impressed with Käsebier’s works that he included six of her photographs in the first edition. In fact, he continued to feature her photographs in subsequent editions. This culminated in 1906 when he mounted an exhibition of Clarence H. White and Käsebier’s works at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession as a prime example of Pictorialist photography by two if its most accomplished photographers.

Post Stieglitz Years

But in 1908, Stieglitz’s approach to photography as art underwent a major shift. He abandoned the Pictorialist movement and denounced it in the strongest terms. In its place he adopted the Modernist method of Straight Photography. Where Stieglitz had showered praise on Käsebier in earlier days, now he denounced her continued commitment to Pictorialism. He also strongly opposed her financial success as a sought-after portrait photographer, believing that goal of art was not financial rewards. Their friendship came to an end although she remained a member of the Photo-Secession group. However, in this year she resigned from the Linked Ring.

Attacks on her continued and in 1911. Käsebier was the subject of a sharply critical assault from Joseph T. Kelley in Photo Works. At the time it was suspected that Stieglitz had put Kelley up to it. A year later Käsebier resigned from the Photo-Secession group.

Nevertheless, Käsebier pressed on. Another of her passions was encouraging women to take up photography as a profession. In 1913 she authored an article for the New York Times on this topic. Her painful relationship with her husband, who had died in 1909, may have influenced her to promote this idea. She was profoundly committed to motherhood as emphasized in so many of her photographs of mothers and their small children. However, she did not idealize the notion of marriage in her photographs but rather portrayed it as a burden in the few photographs devoted to this subject. It was through her independent and self-reliant spirit that she had achieved the enormous success that she enjoyed.

“Yoked and Muzzled” is considered to be Käsebier’s depiction of her marriage.

In addition to encouraging women to take up photography, she taught at the school Clarence H. White founded in Maine.

An ardent Pictorialist photographer throughout her active years, she joined with Clarence H. White in forming The Pictorial Photographers of America in 1916. The organization is still active today and even has a Facebook page although they have transitioned to the digital age. The Williamsburg Art and Historical Center celebrated the 100th anniversary of the organization in 2016 with a show titled “Platinum to Pixel: Pictorial Photographers of America Turns 100.”

Meanwhile, Stieglitz’s didactic personality caused members of the Photo-Secession to start falling away and in 1917 he abandoned it.

Käsebier’s health had been deteriorating since 1905. She was not immune to the stresses in her life and on top of that, her vision and hearing had started to decline. Fortunately, her youngest daughter, Hermine Käsebier Turner, was also a fine photographer and in 1924 she joined her mother in the business. They worked together until 1929 when Käsebier closed her studio and sold all of her equipment.

The last several years of her life she paid less attention to photography and more on supporting Pictorialist photography by participating in exhibitions. A major retrospective of her work was mounted in the Brooklyn Museum. Also, in the same year the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences celebrated the Grand Dame with a one-person exhibition. She was affectionately referred to as “Granny” by many of her colleagues which helped to relieve Victorian gender prejudices while recognizing her natural “tendency to act forcefully on her own behalf.”

Gertrude Elizabeth Käsebier died on October 12, 1934 in the home of her daughter Hermine.

Her Legacy

Gertrude Käsebier was certainly one of the greatest portrait photographers to ever put a camera between her creative eye and her subject. She had the ability to draw out the true selves of her subjects whether they were celebrities, American Indians or simple people off the street.

But it was her passion for portraying the beauty of motherhood that led her to some of her most moving photographs. She romanticized and even idealized the relationship between mother and child.

Her portraits of the American Indian provide us with a personal look into their lives and beings. We see them without pretense or exaggeration.

She was a powerful advocate for women taking up photography as a profession and shared what she had learned in her career by conducting photography classes.

All in all, she played an important role in establishing photography as a fine art.

In 1979 she was inducted into the International Photographers Hall of Fame. hat same year a major retrospective of her work was mounted in the Delaware Art Museum.

In 1991 the New York Museum of Modern Art featured her in an exhibition. And in 2002 her photograph, Blessed Are Thou Among Women, was used on a United States commemorative postage stamp.

Here legacy and influence lives on.

(205)