“We realize as perhaps he [Stieglitz] did not, that the freedom of the artist to create and give the fruits of his work to people, is indissolubly bound up with the fight for the political and economic freedom of society as a whole”.

– Paul Strand

The Early Years

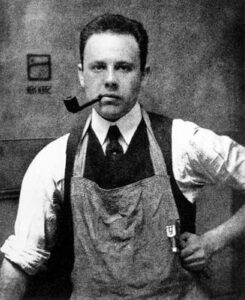

Nathaniel Paul Stransky was born in New York on 10/26/1890 to Bohemian merchants Jacob and Matilda Stransky, German Jews. He was to become a legend among early American photographers whom we now know by the name, Paul Strand.

His father provided for the family by running an enamelware business. When Strand was 12, his father gave him a camera and while this was not the turning point in his life, he was fascinated by it.

Strand spent his high school years in the Ethical Culture School, an educational institution founded in 1878 to provide free, quality education to the children of the poor. By 1880 the school had such a high academic reputation that more wealthy parents wanted to enroll their children, at which time they started charging tuition. In 1903, the New York Society for Ethical Culture became the school’s sponsor. The school awarded over $55 millions in tuition-based financial aid to over 20% of its student body.

Strand joined the school in 1904 where he came into contact with Lewis Hine, a famous documentary photographer who was intent on social reform and whose photos were instrumental in reforming child labor laws in the United States. Hine was to have a strong influence on Strand, both photographically and socially.

In 1907, Strand joined the after-school camera club that Hine founded. One of their field trips was to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery, originally The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 4th Street in Manhattan. At the time, the gallery was a showcase for the American Pictorialist movement photographers as well as European painters like Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Henri Rousseau, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso. The year was 1907 and that, at the age of 17, was the experience that set Strand’s course on a life devoted to photography. Unbeknownst to him at the time, Stieglitz would have a powerful effect on his growth as a photographer and later on he in turn would profoundly influence Stieglitz’s photography.

The Pictorialist Period

I’ve always felt you can do anything you want in photography, if you can get away with it.

– Paul Strand

Strand graduated from the Ethical Culture School in 1909 and went to work as a clerk in his father’s enamelware business. But he pursued his interest in photography by participating in the Camera Club of New York. Three years later in 1911 he opened his first commercial photography business.

His initial plunge into photography was the Pictorialist method which he had been exposed to in the 291 gallery and in which Stieglitz was absorbed during this time. This style attempted to create photographs that resembled paintings in an effort to get photography accepted as a legitimate art form by emulating forms that had been accepted as art for centuries. In keeping with this tradition, Strand experimented with a soft-focus style and gum printing, hallmarks of the Pictorialist movement.

| Strand was transitioning from his Pictorialist style to Modernism when he took this photograph. Many Modernist photographers of his time were intent on photographing the hustle and bustle of the city. Strand took the opposite approach in this photograph. Rather than the press of people, this photograph shows just a few pedestrians walk through New York’s financial district. Towering above them is the ominous presence of the J. P. Morgan & Co. bank building. The long shadows of the pedestrians contrast dramatically with the dark vertical power of the building. |

But Strand was to eventually tire of the Pictorialist tradition, realizing that photography, if it was to be a legitimate art form, must do it on its own terms and not by emulating other established media.

Straight Photography

[Photography] finds its raison d’etre, like all media, in a complete uniqueness of means. This is an absolute unqualified objectivity. Unlike the other arts which are really anti-photographic, this objectivity is of the very essence of photography, its contribution and at the same time its limitation… The full potential power of every medium is dependent upon the purity of its use…

– Paul Strand

The process of change began in 1915. Stieglitz had already tired of the Pictorialist method and adopted the Modernist movement that was rampant in Europe. Strand presented some of his Pictorialist photographs to Stieglitz for critique and they were soundly criticized by the master who challenged Strand to rethink his approach to photography.

As a result of this feedback, Strand launched a process of self-examination, realizing that he needed to develop his own signature technique. He commented at the time, “You may see and be affected by other people’s ways, you may even use them to find your own, but you will have eventually to free yourself of them. That is what Nietzsche meant when he said, ‘I have just read Schopenhauer, now I have to get rid of him”. Strand spent the next two years developing his own style that became known as ‘Straight Photography.’ At its foundation was the lack of manipulation of the photographs. In addition, the camera’s ability to faithfully produce images of reality was celebrated. In Straight Photography, Strand emphasized form, sharp focus, sharp detail, high contrast and rich tonalities.

When Stieglitz saw Strand’s work in 1917, he was greatly influenced by it and mounted a major exhibition of his photographs in 291. He also devoted the last two issues of Photo Work, Stieglitz’s legendary publication, exclusively to Strand. And as the ultimate compliment to Strand’s work, Stieglitz adopted the methods of Straight Photography in his own work.

Street Photography

The portrait of a person is one of the most difficult things to do. It means you must almost bring the presence of that person photographed to other people in such a way that they don’t have to know that person personally, but that they are still confronted with a human being that they won’t forget. That’s a portrait.

– Paul Strand

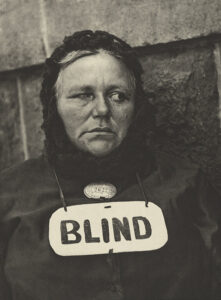

Strand’s social conscience, which was reinforced with his association with Hine, took him to the immigrant ghetto at Five Points Center in New York. He was intent upon making “portraits of people such as you see in the New York parks and places, sitting around, without their being conscious of being photographed. … I felt that one could get a quality of being through the fact that the person did not know he was being photographed … [and I wanted to capture] these people within an environment which they themselves had chosen to be in or were in anyway.”

In order to make candid photographs of his subjects, Strand altered his camera with a fake lens that was 90 degrees to the real one so that people would think he was photographing something else. The real lens was hidden under his arm. And while he was photographing people without their knowledge or consent, he did not want to exploit them. “I always felt that […] I was attempting to give something to the world and not exploit anyone in the process,” he once said. Some of his most moving photographs were taken in this way.

| Strand used his altered camera with the fake lens to capture these candid photographs in the Five Points area in New York. Despite the fact that this blind woman would not have seen Strand, this technique portrayed her as she really were. We see her for whom she truly is and, as was Strand’s intent, we recognize her and cannot forget her. |

Even when he photographed people that knew they were being photographed, we do in fact see something we recognize in them and connect with. “It is one thing to photograph people. It is another to make others care about them by revealing the core of their humanness.”

Abstraction

All good art is abstract in its structure.

– Paul Strand

It was during this time that Strand was influenced by the cubist works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. In an attempt to apply their approach to photography, Strand was the first to use a camera to create purely abstract works of art.

| Porch Shadow was one of Strands first attempts at creating true abstract photography. It was taken while on vacation in a rented cottage in Twin Lakes, Connecticut. Strand separated the photograph from the literal by rotating the image and emphasizing shapes, patterns, stripes, and triangles. |

During a summer in Twin Lakes, Connecticut, he experimented with shapes and shadows, photographing everyday items in ways that they go beyond the literal. He built his pictures, relating shapes to each other, filling the spaces and creating a sense of unity among all of the elements.

Social Consciousness

I photographed these people [on New York streets] because I felt they were all people whom life had battered into some sort of extraordinary interest and, in a way, nobility.

– Paul Strand

In the 1920s Strand became involved as cinematographer in his first motion picture, Manhatta, based on Walt Whitman’s book of the same name. This marked a new direction in Strand’s life, a direction through which he would express his social conscience. For the rest of the decade, he worked as a freelance cinematographer.

In 1932, Strand received an invitation from Carlos Chavez, the eminent Mexican composer and conductor and director of the fine arts department at the Secretariat of Public Education, to come to Mexico City. This was to be a period of intense creativity and productivity. During this time the concept of the “collective portrait” emerged in which Strand captured the soul of Mexico in photographs of individuals, still lifes and studies of architecture and religion.

He was invited to show his work at the Sale de Art and the show opened in 1933. At the same time, he was appointed to the Mexican Department of Fine Art as Chief of Photography, Cinematography and Secretariat of Education. His time in Mexico culminated in a collaboration with Emilio Gomez Muriel and Academy Award-winning director Fred Zinnemann in the film, “Redes” (“The Wave”), released in 1936. His Mexico photographs were so important that they were included in his first exhibition at the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1937.

In 1936, Strand joined with Berenice Abbott to establish the Photo League, an organization of New York photographers initially dedicated to providing the socialist press with trade union activities and political protests. This evolved into projects that highlighted working class communities. At the end of World War II, the Photo League caught the attention of the FBI which saw them as pro-communist, subversive and anti-American. In 1947, the league was officially placed on a U.S. Department of Justice blacklist of subversive organizations. The accusations continued which ultimately caused the League’s demise. In 1951 it was disbanded.

Earlier in 1934 Strand was also involved in the founding of Frontier Films, a documentary film company devoted to pro-labor causes. Of the seven films produced by Frontier Films, Strand’s participation was limited to Native Land which was produced in 1942 and narrated by Paul Robeson. This film was controversial in that it depicted the struggle of trade unions against the union-busting efforts promoted and supported by large corporations. As a result, it was also considered by many to be subversive and anti-American. Frontier Films ultimately joined the Photo League on the Justice Department’s list of subversive organizations.

There is no record of Strand ever being a member of the communist party. However, many of his friends were communists or accused of being such and his socialist, anti-fascist political views are strongly represented in the subject matter he chose for his films and later photographs. Native Land was probably his strongest film statement and, because of its exposure of violence against minorities and the poor, was perceived by many as divisive. As a result, it received limited showings in this country. However, in June of 1949 it was presented at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia. Now the landmark film has been remastered and available from several academic and commercial sources.

These developments were a prelude to his departure from the United States to live the rest of his life in Europe.

A New Beginning in Europe

I think of myself as an explorer who has spent his life on a long voyage of discovery.

– Paul Strand

It was during the McCarthy era that Strand became disenchanted with the conservative political climate in the United States and relocated to Europe in 1950 where he took up residence in Orgeval, France. He spent the rest of his life there with his third wife, Hazel Kingsbury. They were married in 1951. Kingsbury already had a photographic background as she was a staff photographer for the Red Cross, beginning in 1945 where, among other things, she photographed the carnage of the war.

Strand’s work changed to the notion of the ‘collective portrait’ that he developed while in Mexico. These were manifest in a collection of publications, each of which featured a specific land and culture. The first was of France, La France de Profil, published in 1952. His second publication, Un Paese. came in 1955 and featured the Luzzara and Po River valleys of Italy. Next, he turned his attention to the Outer Hebrides and in 1962 published Tir a’Mhurain. Following that his interest was directed to Africa and in 1969 he published Living Egypt. But he had one more publication, again in Africa. In 1976 was his last book, Ghana: An African Portrait.

Paul Strand died in Orgeval, France on March 31st, 1976. He was survived by his wife, Hazel Kingsbury. And in 1984, his contribution to photography was recognized with his induction into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Paul Strand’s importance is demonstrated by the fact that, to this day, retrospectives of his work continue to be mounted in leading museums around the world and his original prints continue to be sought after by collectors and are sold for five and six figures in auction houses such as Christie’s.

Paul Strand’s Legacy

What is it about Paul Strand’s photographs that make them so admired and that places him among the greatest photographers of all time? Was it because he promoted Straight Photography or was the first to intentionally make significant abstractions with a camera? Or was it the intensity and honesty of the candid photographs he made of immigrants in Five Points or in all of his portraits for that matter? Perhaps it was his concern for the poor and downtrodden.

In his dedication to Straight Photography, Strand diligently explored the limits of the ability of the camera in creating art, finding its strength in its ability to represent the world with clarity and purity. But it was in the hands of a master such as Strand that photography reached its full potential. He was intent on not expressing himself through his photographs but rather creating a true, honest and respectful rendering of his subject, whether it be people, architecture, landscapes or machines. Perhaps, one of his greatest strengths was how he carefully built his pictures, paying close attention to how the space was filled and how unity was created. He was meticulous, spending hours, days and even weeks building some of his photographs.

It helps to have a sense of who Paul Strand was, his commitment to photography, his rigorous development and application of the philosophy of Straight Photography, his deliberate care in building his photographs, and his commitment to social justice to better understand his work. When you look into the eyes of those he photographed you do indeed recognize their humanity.

Join me on a workshop and explore the wonders of nature with your camera.

(912)