There’s no question about it; photography is very technical. There are many technical skills that must be mastered to become a proficient photographer. And they didn’t all just crop up when digital cameras came on the scene. Film cameras required a great deal of technical know-how also.

If you were taking a grand landscape photograph back in the days of film, a composition that had a very interesting foreground and a spectacular background, you had to know how to control your depth of field so that the foreground and the background and everything in between would be in focus. This required a technical knowledge of the three factors that affect sharpness; those being, focal distance (the distance from the camera to the object you’re focusing on), the focal length of the lens and the f-stop.

Exposure in the film era was perhaps even a little more intimidating. Your ISO was determined by your film and you selected that when you purchased it. But you had to set your shutter speed and your f-stop manually. Shutter speed wasn’t too hard to understand. If you decrease the length of time the shutter was open, you decrease the amount of light that passed through the lens by the same amount. A shutter speed of 1/30 of a second let twice as much light through the lens as 1/60 of a second. Pretty simple.

But f-stop didn’t make any sense at all. If your f-stop was f/8 and you wanted to double the amount of light coming through the lens, you set it to f/5.6. The amount of light was doubled but the number was smaller. And it wasn’t what you might intuitively have expected it to be, namely, f/4. It could be a bit baffling. And the only way to get a grasp on it was to memorize these weird numbers. With film you were stuck with manual exposure and there was no getting around it. With digital you can use one of the automatic exposure modes so you can get away without fully understanding this f/stop stuff. But it’s still best if you do.

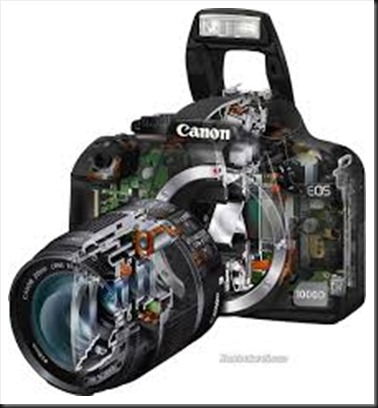

The coming of the digital camera introduced a whole new level of complexity. In the film age the camera was a simple mechanical device. You were responsible for doing practically everything – deciding where to focus, the shutter speed to use and the f-stop to use. The only role the camera played was to open the shutter for the precise length of time that you specified when you set the shutter speed.

The coming of the digital camera introduced a whole new level of complexity. In the film age the camera was a simple mechanical device. You were responsible for doing practically everything – deciding where to focus, the shutter speed to use and the f-stop to use. The only role the camera played was to open the shutter for the precise length of time that you specified when you set the shutter speed.

When we cradle a digital camera in our hands we are holding a sophisticated, powerful computer. Like computers everywhere, they can take over many of these functions for us like focusing and setting the exposure. But this added convenience comes at a cost. You get a great deal of flexibility and control but now, in addition to mastering the basics that you needed to know for film, you also need to know how to set the camera mode, set the metering mode, switch between auto and manual focus, use exposure compensation, auto exposure bracketing, high ISO noise reduction and on and on. I’m just getting started.

The great thing about the digital camera revolution is that it gives us unprecedented control in creating high quality images that express what it is we want to say. And for some of us with a technical background, picking this up is pretty straightforward. But for those that are not as technical it can be a bit difficult.

So, there is a huge technical component to digital photography. And in spite of its advantages, there’s a pretty significant downside. I can explain it best if we talk for a moment about the human brain.

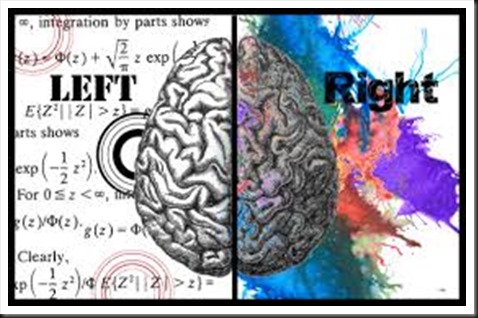

You’ve seen pictures of the brain and the most outstanding feature of the brain is that it is separated right down the middle into two halves. There are two sides to the brain – the left brain and the right brain. Now while they look virtually identical, they play very different roles that affect the way we experience the world.

You’ve seen pictures of the brain and the most outstanding feature of the brain is that it is separated right down the middle into two halves. There are two sides to the brain – the left brain and the right brain. Now while they look virtually identical, they play very different roles that affect the way we experience the world.

The left brain for most of us is our speech center. Language emanates from the left brain. It’s also our problem-solving center. The left brain is analytical and detail oriented. Linear thinking is also the domain of the left brain. The left brain it turns out is critical to our day-to-day life.

The right brain plays a totally different role in our existence. It is holistic. Instead of focusing on the details it takes in the big picture. It’s also intuitive. Have you ever had an ah hah moment, a moment when you’ve had a flash of inspiration and insight? That came from your right brain. Creativity also resides in your right brain.

So, back to photography. How does this knowledge of the roles of the left and right brain help us understand the creative process? Well, we’ve been discussing the technical requirements of photography. They are problem-solving in nature and thus clearly the purview of the left brain. And with so much of photography coming from our left brain, it’s easy to imagine how the left brain can encroach on the creative side of photography.

Take composition for example. I consider composition to be a largely creative activity because much of what a photograph expresses is achieved through a strong composition. But so often composition is approached analytically. And that’s not surprising. Virtually all of the books I’ve read on composition have approached the subject by breaking composition down into its component parts. You have rule of thirds, line, shape, form, texture pattern and color. Analyzing something like this and breaking it down is very much of a left brain activity. And since there’s already so much problem-solving, so much left brain activity in photography it’s not surprising that it would spill over into creative activities such as composition.

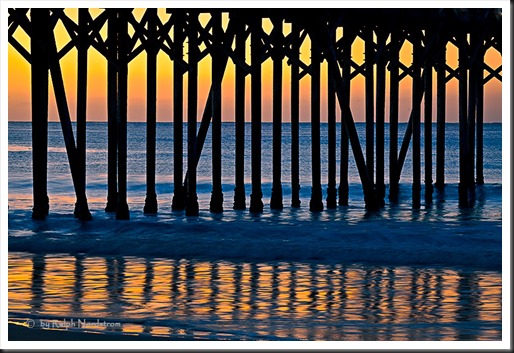

So often we see an image in terms of its leading lines and layers and textures and rule of thirds that we lose sight of its emotional content. Don’t get me wrong. The compositional principles that we study are very important. They are the vocabulary we use to give a photograph its message. I call this the creative vocabulary. Just like the poet who has a larger vocabulary can use it to express greater things in his poems, a larger creative vocabulary permits us to express more in our photographs. But having a large vocabulary doesn’t necessarily make a great poet. And having a large creative vocabulary doesn’t necessarily lead to a strong compositions. We need to approach composition holistically, from the right brain. We need to feel the composition. We need to feel it in terms of its balance, unity and visual tension. These are holistic perspectives.

In this light then, photography becomes a fascinating interplay between the technical and the creative. It’s been said that creativity is 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration. The 10% is the contribution from our right brain and the 90% is the contribution from our left brain. A great photograph starts when you feel that powerful moment of inspiration in the field, when something grabs hold of you and stops you in your tracks. You feel it with your right brain and have a sense of what you want to convey but the problem is, how do you capture that? And that’s where the left brain comes in. You’ve had your 10% of inspiration. Now it’s time to get on with your 90% of perspiration. The first thing I do is set up the camera and try to compose the image. I’m aware of leading lines and S curves and rule of thirds and all of that stuff but I really strive for balance, unity and visual tension. Both brains are contributing but the right brain is the most active. Once I get a composition that conveys my intent it’s time to switch on the left brain. The next thing I focus on is, well, focus. I think about depth of field and how to achieve the level of sharpness that supports my creative vision. Once I have that down it’s time to think about exposure. Do I anticipate any exposure problems or is it straightforward? If there are exposure problems, how can I solve them – under expose, HDR, grad-ND? Eventually the time comes to press the shutter. When the camera has finished doing its thing I checked the histogram. Did I get the exposure right? If so, go on to the next shot. If not, corrected and try again.

It may seem that the interplay between the technical and the creative is pretty natural, that it occurs pretty easily. But it’s not. And again, it’s because of the way our brains work. For most of us the dominant side of the brain is the left side. It’s very noisy, demanding our attention all the time. And it drowns out the right side which is very quiet and subtle. The right brain is over there quietly doing its thing but much of what it does for us goes unnoticed. It’s not until we have those periods of inactivity in our left brain that we hear the soft, quiet voice of the right brain.

So the trick is to learn how to quiet the left brain when we need to hear the right brain. And there are several things that we can do. For example, when arriving at a location that we want to photograph, resist the urge to grab the camera and tripod and photograph the first thing you see. Rather, set your gear down and wander around, taking it all in. Don’t go on an urgent hunt to find something but instead let it come to you. Often times I have to tell myself to stop thinking. Don’t get caught up in looking at details but look at nothing and everything at the same time. Open your awareness to all of your senses. Don’t force it; just let it happen.

And when something does come to you, when something speaks to you, don’t rush into action. Do this simple thing. Think of an adjective that captures what you are experiencing. I said it was a simple thing; I didn’t say it was easy. But with practice you can do it. Once you are centered on the experience you are having, your right brain has done its job and you can turn the rest of the process over to your left brain.

Our love of photography and the world we photograph has set us on a journey. We seek the joy of experiencing the wonders of nature. We hope to capture it in our photographs and share it with others. We are gratified when we bring pleasure and joy to ourselves and others through our art. Our journey is one of personal growth and self-discovery. We pass through stages and, no, the stages cannot be analyzed and precisely defined nor do they come in a set sequence.

Our love of photography and the world we photograph has set us on a journey. We seek the joy of experiencing the wonders of nature. We hope to capture it in our photographs and share it with others. We are gratified when we bring pleasure and joy to ourselves and others through our art. Our journey is one of personal growth and self-discovery. We pass through stages and, no, the stages cannot be analyzed and precisely defined nor do they come in a set sequence.

But for many of us we reach a point where we want to become more creative, where we want to unleash the artist in us. My hope is that if you are at that point or when you reach that point, these thoughts I’ve shared with you will help you take your photography to the next level.

We do photography workshops. Come on out and join us. Click here to check us out.

You can also check out our photography. Click here.

(2608)

Excellent, post. One of the things I love about contemplative photography is that it engages both sides of the brain so completely.

Thanks for the comment Alison. I really like that aspect of photography too.