Photography is Mechanical

Between 1840 and 1860 the growth of photography was all about science. The development of light sensitive media was dependent on a few brilliant scientists figuring out how to make them and experimenting with what would work best. And Kodak was decades away from inventing roll film and the camera it came in. If you wanted to be a photographer you had to master the chemistry of your chosen medium and in some cases, as we shall soon see, you had to be able to take your darkroom with you.

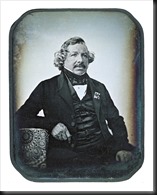

The first workable medium, the daguerreotype, was discovered by Louis Daguerre and made publicly available in 1839. His  process was rather remarkable. It started with a metal plate that had a coating of silver on one surface. The most commonly used metal for the plate was copper. Next the silver side of the plate was polished to a mirror finish. The silver was then sensitized by exposing it to halogen fumes creating silver halide crystals that were sensitive to light. This had to be done in the dark or, at most, illuminated by a yellow safe light. The halogens that were eventually used were iodine, bromine and chlorine. From this point on the sensitized plate must be kept in the dark.

process was rather remarkable. It started with a metal plate that had a coating of silver on one surface. The most commonly used metal for the plate was copper. Next the silver side of the plate was polished to a mirror finish. The silver was then sensitized by exposing it to halogen fumes creating silver halide crystals that were sensitive to light. This had to be done in the dark or, at most, illuminated by a yellow safe light. The halogens that were eventually used were iodine, bromine and chlorine. From this point on the sensitized plate must be kept in the dark.

Depending on the sensitivity of the plate, the brightness of the light and the quality of the lens, exposures ranged from a few seconds to many minutes. The latent image on the plate was developed by exposing it to fumes of heated mercury (a dangerous procedure at best) and the image appeared. To remove the remaining unexposed silver halide crystals the plate was washed in a mild solution of sodium thiosulfate. And now the image could be brought into the light and enjoyed.

As I’m sure you can appreciate, the discovery of this process was a brilliant scientific achievement. It must have required a lot of  trial and error.

trial and error.

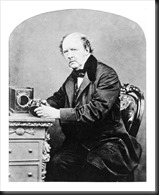

But it wasn’t long until William Henry Fox Talbot introduced the calotype process in 1841. There was a lot of chemistry in this method too, much more than with the daguerreotype. Let me outline it for you. High quality paper was brushed on one side with a solution of silver nitrate. After drying, the paper was dipped in a solution of potassium iodide and dried again. The paper was not light sensitive yet. Just before use it was brushed with “gallo-nitrate of silver”, a mixture of silver nitrate, acetic acid and gallic acid. Now it is light sensitive and ready to be exposed. After exposure it was developed by brushing on more gallo-nitrate of silver solution while gently warming the paper. Finally, the image was ‘fixed’ by either washing the paper in silver bromide or rinsing it in sodium thiosulfate.

Whew! What a lot of work. The great advantage of the calotype was that multiple prints could be made from the paper negative. The disadvantage is that the prints were blurry because the negative was paper.

The third major scientific development was the use of collodion. This is a highly flammable syrup of cellulose to which nitrogen had  been chemically bound. In 1851, Frederick Scott Archer figured out how to use collodion for photography. The process went something like this. Take a glass plate and clean it exceedingly well. Pour collodion salted with iodine or bromine on the glass plate and tilt the plate till it is entirely covered. In a darkroom immerse the plate in a solution of silver nitrate to sensitize it. Load the plate into the camera, bring the camera outside to make the exposure while the collodion is still wet. Run back into the darkroom to develop the plate in ferrous sulfate-based solution and fix the image, again with sodium thiosulfate. All of this had to be done while the collodion was still wet, roughly 10 minutes from start to finish. Hence the name, wet plate.

been chemically bound. In 1851, Frederick Scott Archer figured out how to use collodion for photography. The process went something like this. Take a glass plate and clean it exceedingly well. Pour collodion salted with iodine or bromine on the glass plate and tilt the plate till it is entirely covered. In a darkroom immerse the plate in a solution of silver nitrate to sensitize it. Load the plate into the camera, bring the camera outside to make the exposure while the collodion is still wet. Run back into the darkroom to develop the plate in ferrous sulfate-based solution and fix the image, again with sodium thiosulfate. All of this had to be done while the collodion was still wet, roughly 10 minutes from start to finish. Hence the name, wet plate.

Now, if you were doing this in a studio, no problem. Your darkroom is in the next room. But imagine doing this outside, far from civilization.  Your darkroom must be in a light-tight wagon hauled around by a team of horses. The photographer had to quickly make the wet plate, load it into his camera, run outside, compose an image, expose it, run back inside and develop the image. Mathew Brady, the great chronicler of the Civil War, used the collodion wet plate process for his photographs. It wasn’t just the long exposures that prevented him from taking photographs of the action. There was no way he could wait half an hour for the right moment. If he tried the collodion would dry and was no longer light sensitive.

Your darkroom must be in a light-tight wagon hauled around by a team of horses. The photographer had to quickly make the wet plate, load it into his camera, run outside, compose an image, expose it, run back inside and develop the image. Mathew Brady, the great chronicler of the Civil War, used the collodion wet plate process for his photographs. It wasn’t just the long exposures that prevented him from taking photographs of the action. There was no way he could wait half an hour for the right moment. If he tried the collodion would dry and was no longer light sensitive.

I’ve gone into quite a bit of detail here because I want to emphasize how photography’s roots are deeply anchored in science. That limited photography to those that could master the complex chemistry that was involved in taking a picture and producing prints. And because it required so much science and the daguerreotypes or photographs were created with a mechanical device, the results were widely considered to be mechanical and anything that was mechanical could never be art.

The wet plate was eventually replaced with a dry glass plate with a gelatin emulsion. And by 1889 Kodak introduced rolls of film that were coated with a gelatin emulsion. This is the year the Kodak #1 camera was introduced. It came with a roll of film already loaded, a roll that could take about 120 pictures. When all of the pictures were exposed you sent the camera back to Kodak where they would develop the film and make prints. They returned the developed film, prints and camera with a new roll of film. Kodak’s slogan was, “You press the button, we do the rest.”

Now photography was available to the masses. You didn’t have to have all the equipment need to create, expose, and develop your negatives and make your prints. And more importantly, you didn’t need the knowledge of chemistry to do all that. And, given how convenient Kodak made it, the masses didn’t take pictures with the same care as the professionals. All of sudden, millions of snapshots were taken every year.

This muddied the art waters even more and strengthened the notion that photography could never be a medium for artistic expression. In fact, the poet Charles Baudelaire went so far as to say, “This industry, by invading the territories of art, has become art’s most mortal enemy.” The debate got a little heated, wouldn’t you say.

Photography is Art

But, thankfully, there were those that disagreed. A movement germinated that made the logical conclusion that if you want photography to be art, it makes sense to adopt the techniques and principles of painters who without question have been producing art for hundreds of years. If photographs could be made that used techniques that reproduced the same effects that a painting had, that would surely be art.

The paintings of the masters of that time produced emotions, surprise, discovery, insights in their viewers. They told stories, they recounted events in history and mythology, they revealed inspiring landscapes. But straight photographs were representational and nothing more. They documented events and showed unadorned reality. There was no artistic interpretation. But some photographers were intent on developing processes and techniques that would enable photographs to create these same lofty images.

A movement was emerging and became known as the Pictorialism movement. Although it has been associated with controversy over the years, it had a run of nearly 100 years. Not bad for something that took so much heat. Alison Nordström, Senior Curator of Photography at the George Eastman House, describes it this way. “The effort was to claim that this machine, this camera, could make art. And one of the easiest ways to make things that people understood as art was to make things that looked like art. So unlike snapshots, pictorialists’ photographs looked like paintings and charcoal drawings and etchings.”

Figure 14 – Fading Away

The first photographer to use the word ‘Pictorial’ was Henry Peach Robinson in his book published in 1869 titled Pictorial Effect in Photography: Being Hints On Composition And Chiaroscuro For Photographers. In the book he not only describes composition and the use of light and contrast in great detail, using many paintings as his examples, but he also promotes the idea of using multiple negatives to produce a print, a technique known as combination printing.

This photograph, Fading Away, is a good example and one of Robinson’s most popular work. The subject is heart rending. It is a photograph of a young women dying of consumption. Even in its day it was criticized for its morbid subject matter that was not considered by some as appropriate for photography. And yet, it was one of Robinson’s most popular photographs with his Victorian audience. They apparently loved morbid photographs and paintings. The print was made from five negatives and took Robinson three years to perfect.

Manipulating the images to reduce or eliminate the merely representational nature of straight photography became common practice. Negatives were double exposed, painted and scratched with needles.

A photographer that preceded Robinson in combination printing was the Swedish photographer Oscar Gustave Rejlander (1813 – 1875). He exhibited his most memorable work at the Paris Exhibition in 1855 titled The Two Ways of Life. It was an allegorical work comprise of 32 of his images and depicts a man being torn between vice and virtue by good and bad angels. It sparked controversy to say the least!

Figure 15 – The Two Ways of Life

Pictorialism made it to the United States in 1902 when Alfred Stieglitz broke away from The Camera Club of New York with several others including Gertrude Käsebier, Alvin Langdon Coburn and Frank Eugene. They formed a group they called the Photo-Secessionists. They exhibited their works in a space donated by Edward J. Steichen and named it The Little Gallery of the Photo-Secession, later to be known as the famous 291 Gallery.

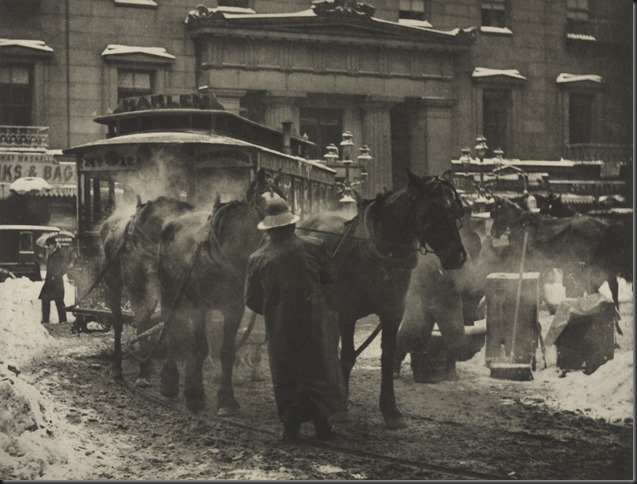

Figure 16 – The Terminal

Stieglitz was intent on establishing photography as a legitimate art. He ran the gallery and published a journal titled Camera Works. He was tireless in his pursuit and in 1924 he achieved his goal when he donated 27 of his photographs to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Photography was finally acknowledged as a true art form.

His photograph The Terminal is significant in two ways. It has some of the atmospheric effects that were appreciated in pictorial photography although the subject matter is a preview of the straight photography movement that was to come. But it was also shot with a handheld 4X5 camera. This is important because millions of ‘snapshots’ were being taken with Kodak handheld cameras and Stieglitz demonstrated that a handheld camera can also create art.

Pictorialism continued to be a strong movement in photography, influence photographers until the 1920s when it began to fade. But it wasn’t until the end of the Second World War that it pretty much disappeared from the art scene.

Some of the great photographers that were expanding the creative breadth of photography in the 20th century got their start with pictorialism. These included Ansel Adams, Imogene Cunningham, and Edward Weston.

When pictorialism fell from grace, it fell with a loud crash. For quite some time it was looked upon with disdain and embarrassment. John Szarkowski, the legendary Director of Photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art, created a monumental exhibit in 1964 titled The Photographer’s Eye. The exhibit was published in a book and reprints are still available to this day. In the introduction, Szarkowski makes this comment: “The elaborate nineteenth century montages of Robinson and Rejlander, laboriously pieced together from several posed negatives, attempted to tell stories, but these works were recognized in their own time as pretentious failures.” Even Stieglitz eventually said, “It is high time that the stupidity and sham in pictorial photography be struck a solarplexus blow…” when he moved on to ‘straight photography.’

But looking back, the importance of individual expression is just as relevant today as it was then. The notion of creating photographs that are expressive, that stimulate emotions, which provide insight, and which enrich our lives is the highest tradition we can strive for with our photographs today. The tools that are available to us today to achieve these lofty goals are so much more powerful than those the pictorialists had. Our ability to express ourselves is therefore greatly enhanced. But the goal is the same: to create photographs that are an expression of the unique person each of us is and the exclusive way we see and think about the world through which we move.

This is the third in a series on the emergence of art in photography. If you missed the first two, here are their links:

In the Beginning There Was a Camera but No Film

The First Photographers: 1840 – 1860

You are invited to leave a comment. We would like to hear from you.

Join us on one of our photography workshops.

Or, check out the photographs in our gallery.

(731)