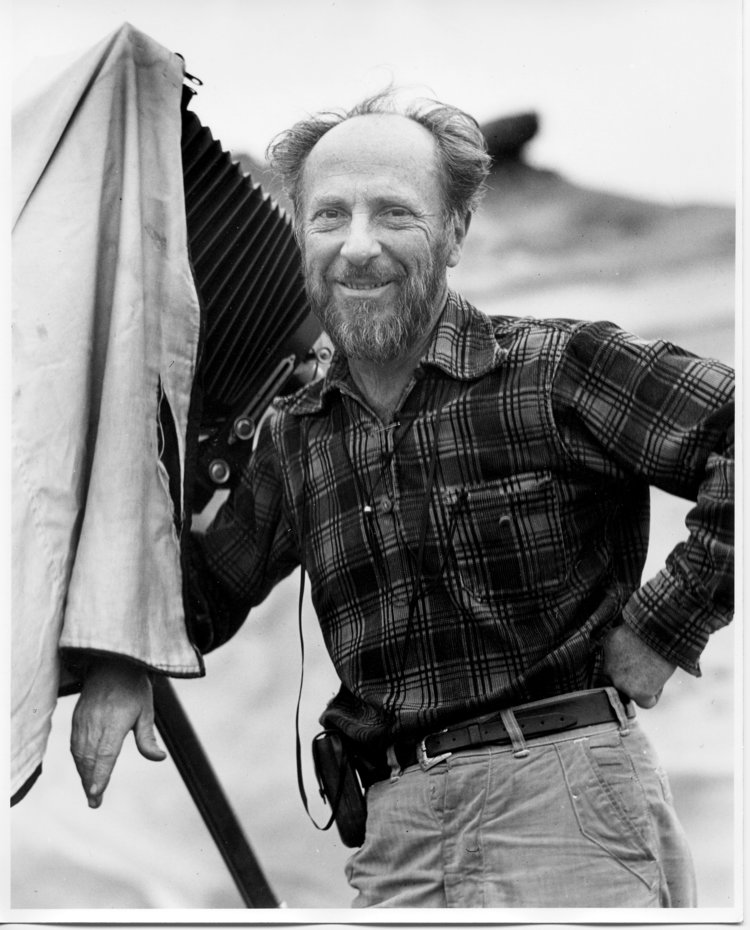

“One does not think during creative work, any more than one thinks when driving a car. But one has a background of years – learning, unlearning, success, failure, dreaming, thinking, experience, all this – then the moment of creation, the focusing of all into the moment. So I can make ‘without thought,’ fifteen carefully considered negatives, one every fifteen minutes, given material with as many possibilities. But there is all the eyes have seen in this life to influence me.” – Edward Weston

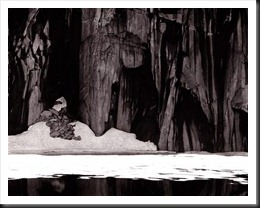

| Note: Not much of Weston’s photographs are in the public domain. Therefore, I have include links to his more important photographs so you can enjoy them. |

Early Life

On March 24, 1886, Edward Henry Weston was born in Highland Park, Illinois into an intellectual family. His father, Edward B. Weston, was an obstetrician and his mother, Alice J. Brett, was a Shakespearean actress. His mother died when he was only five years old and little Edward was raised mostly by his sister Mary who was fourteen years old at the time. Weston called her “May” or “Maisie. They would develop a close relationship which lasted throughout the years.

His father remarried when Weston was nine but neither he nor his sister got along with their stepmother or stepbrother.

When Weston was 11, Mary married and relocated from the Midwest to Southern California, settling in Tropico (later renamed to Glendale). Once Mary left, Weston’s father devoted most of his time to his new wife and her son. He had no interest in books or school and dropped out. He also had a lot of time on his hands and spent it mostly by himself in his room.

In 1902, while on vacation on a farm in Michigan, his father gave him his first camera, a Kodak Bulls-Eye No. 2 for his 16th birthday. His dad included a note which read in part, “you’ll not have to change anything about the Kodak. Always have the sun behind or to the side—never so it shines into the instrument. Don’t be too far from the object you wish to take, or it will be very small. See what you are going to take in the mirror. You can only take twelve pictures, so don’t waste any on things of no interest.”

Continue reading “Edward Weston”(660)