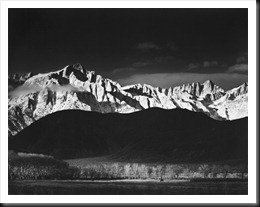

“I tried to keep both arts alive [concert pianist and landscape photographer], but the camera won. I found that while the camera does not express the soul, perhaps a photograph can!” ~ Ansel Adams

The Early Years

On February 20, 1902, Ansel Easton Adams was the only child born to Charles Hitchcock Adams and Olive Bray Adams in San Francisco, CA. His ancestors immigrated from Ireland in the early 1700s and his grandfather was a wealthy timber baron, a business which his father eventually inherited. It is ironic that Adams detested the timber industry later in life.

At the age of 4 the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 hit. The Adams family house made it through the initial quake unscathed, but Adams’ father thought it best if they sit out the aftershocks outside. A particularly large aftershock caught Adams by surprise, knocking him down. He landed face down against a brick wall and broke his nose. A physician suggested that it would be best to wait until Adams matured to set the broken nose. Later in life, Adams said, “apparently I never matured, as I have yet to see a surgeon about it.”

Adams was a problem child. He was sickly, sometimes spending as much as a month in bed. His Aunt Mary gave him books to occupy his time. One was the Heart of the Sierras which apparently planted an interest in these magnificent mountains in his young mind.

When he started school, he was so rebellious that he got expelled from one school after another. Finally, when Adams was 12, his father faced the inevitable and withdrew him from school for a year. A private tutor was hired so that Adams could continue his education. During his time, he was exposed to the works of the great artists. This lasted for one year before he returned to Mrs. Kate M. Wilkins Private School where he graduated from the 8th grade on June 8, 1917.

During this time Adams started playing the piano. At first, he was self-taught but when he was 12, he started receiving lessons. The discipline of daily practice apparently helped him to gain some control over his disruptive behavior. Adams commented about that time. “The change from a hyperactive Sloppy Joe was not overnight, but was sufficiently abrupt to make some startled people ask, ‘What happened?’ I still recall that the Bach Inventions taxed my concentration, especially when a sunny breeze carrying the sound of the ocean stole through the open window.” As he progressed, his passion for the piano continued to grow so that he planned on becoming a world-class concert pianist.

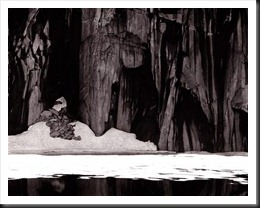

However, the tide started to change imperceptibly. In 1916 he persuaded his “Uncle Frank” to take him to Yosemite, a destination that he was inspired to see from the books his aunt had given him while he laid ill in bed. And at the same time his father gave him is first camera, an Eastman Kodak Brownie box camera. It was on that trip that he took his first photographs of Yosemite. He later commented, “The splendor of Yosemite burst upon us, and it was glorious. There was light everywhere. A new era began for me.” That was the first of an annual pilgrimage to Yosemite that would continue throughout his life. But he still planned on being a concert pianist.

Continue reading “Ansel Adams”(364)