“You know, so often it’s just sticking around and being there, remaining there, not swooping out in a cloud of dust: sitting down on the ground with people, letting children look at your camera with their dirty, grimy little hands, and putting their fingers on the lens, and you just let them, because you know that if you will behave in a generous manner, you are apt to receive it, you know?” – Dorothea Lange

Early Years

Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn was born on May 26, 1895 in Hoboken, NJ to Heinrich Nutzhorn and Johanna Lange. Her father was a lawyer, born of German immigrants. Her mother was a soprano concert singer and later a librarian.

She grew up in Manhattan’s Lower East Side and attended public school at PS 62 on Hester Street. She didn’t particularly like school and often skipped classes. School didn’t become any easier for her when, at the age of 7, she contracted polio. She survived but was left with a withered right leg, a twisted, crabbed right foot and a limp that would be with her the rest of her life. You can imagine the teasing she got from her fellow classmates. Even her mother was ashamed to take her out in public. Lange expressed her attitude about her disability this way.

“I was physically disabled, and I don’t think anyone who hasn’t been semi-crippled knows how much that means. I think it perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me. It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me. All those things at once. I’ve never gotten over it, and I am aware of the force and the power of it.”

When she was twelve, her father abandoned their family. It’s not known why but he was never heard from again. Lange never spoke of him. That is when her mother took a job as a librarian and the family went to live with their grandmother, Sophie.

Two nights a week her mother had to work late, and Lange had to walk home alone through the Bowery. It was a nasty place filled with drunks and thieves and was known as the “Thieves Highway.” Lange developed a way to avoid drawing attention to herself which served her well later in her career.

Lange went on to high school, but she was already showing an interest in photography. After classes she would go to the library to study but instead, looked at books of photographs. When she graduated from high school in 1913, her mother saw her grades and, because they were not good, was concerned for her future.

It was then that Lange told her mother she was interested in becoming a photographer, even though she had never taken a photograph and didn’t own a camera. But instead of supporting that, her mother intervened thinking she should pursue a more reliable occupation and enrolled her in the New York Training School for Teachers.

In 1916 she was hired by Mrs. Spencer-Beatty as a printer, photo retoucher and staff photographer to work in her photo studio at 461 Fifth Ave., New York, N.Y. It was then that she took her first family portrait, launching that period of her photographic career.

In 1917 she attended Clarence H. White’s photography course at Columbia University. With the help of a fellow classmate, she built a darkroom out of a chicken coup behind her home.

In 1918 she and a friend, Fronsie Ahlstrom, made plans to see the world. They collected their money and set out for the West. But they only made it as far as San Francisco where they were robbed. Lange got a job as a photofinisher and selling camera gear at Marsh and Company. It was while working there she met Roi Partridge, Imogen Cunningham’s husband. The three of them hit it off and Lange was now connected with the San Francisco art community. Among these new friends, Lange felt a freedom to be the person she wanted to be and do the things she wanted to do. To sever the ties with her past, she dropped her father’s last name and adopted her mother’s maiden name – Lange.

Among her circle of bohemian friends was a wealthy businessman who loaned Lange the funds to set up a portrait studio. She quickly developed a thriving business photographing the socially elite of San Francisco.

She Becomes a Photographer

With her portrait studio, Lange was doing well. And her friendship with Cunningham and Partridge put her in an exciting circle of artists, not to mention the bohemian lifestyle which suited her well. One of the artists she came in contact with was Maynard Dixon who is best known for his paintings of the American West. Dixon had already established a name for himself with his works selling in galleries in California and Arizona and his illustrations featured in magazines and numerous books.

They hit it off and were married on March 21, 1920. Lange proved to be a significant influence on Dixon’s art. By the time their first son, Daniel Rhodes Dixon, was born on May 15, 1925, Dixon’s style had changed dramatically. His paintings emphasized design, color and self-expression. They became simplified and distilled, infusing them with more power. On June 12, 1828, their second son, John Eaglefeather Dixon, was born.

The Great Depression

In the summer of 1929, while vacationing in Lone Pine, CA, they were hit by a thunderstorm in the Sierra Nevada mountains. During the storm, Lange had a spiritual awakening that she was supposed to photograph all kinds of people, not just the wealthy. Shortly after that the stock market crashed and the Great Depression was on. As it gained momentum in the early ‘30s it became something that Lange could not ignore.

In late 1931, Lang, Dixon and their two sons moved to Taos, NM to live with a group of artists. But as the depression deepened, they returned to San Francisco where they gave up their mutual home and lived in their separate studios. Their businesses were were not doing well and they needed to pursue all the work they could find. When they were not at home they had to board out their children.

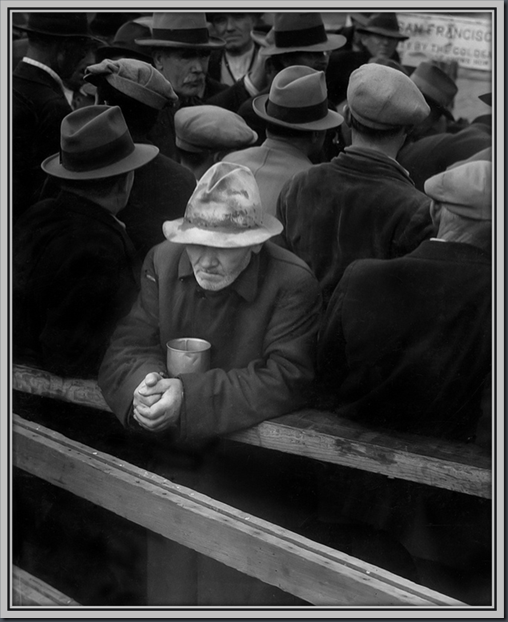

From her San Francisco studio window, she couldn’t help seeing the despair that was growing in the street below. In 1933, accompanied by her brother Martin, she ventured into San Francisco’s Mission District, overflowing with the homeless, hungry and unemployed. They made their way to the White Angel breadline, a soup kitchen founded and run by a widow named Lois Jordan that offered free meals to the unemployed and destitute. Jordan had no resources of her own but was able to rely on donations. She was so successful that over a three-year period she provided more than one million meals.

On Lange’s very first day of photographing the desperate crowds, she made her most important and iconic photograph, White Angel Breadline. The photograph was at once devastating and beautiful. She had captured the face of the Great Depression. The man is weary. His cup is empty. His individuality is obscured by the brim of his hat. He is isolated from the others on the breadline. It is a poignant yet respectful portrait of hopelessness and despair.

On May Day of that same year, there was a demonstration in the San Francisco Civic Center. Lange was there with her camera. But her approach was far different from traditional photojournalism. Lange was sensitive to how facial expressions and body language communicated the states of mind of those she photographed. As a result, instead of showing the magnitude of the protest, she captured the impact on individuals. This was a far more powerful way of communicating what the depression was doing to the country.

In 1934, Willard Van Dyke saw some of Layne’s photographs including those from the May Day demonstration. He deeply admired her work and invited her to contribute some of her photographs to a exhibition he was mounting in his gallery. Paul S. Taylor attended the exhibition and saw Lange’s photographs. He too was deeply impressed. He was working on an article for Survey Graphic magazine and realized her photographs would convey more powerfully what he was trying to say in words. This was the beginning of their collaboration. Later that year Survey Graphic edition was published with one of Lange’s photograph on the cover.

Taylor was a professor of agricultural economics at the University of California, Berkeley. He received a position in the California State Emergency Relief Administration (SERA) to study workers arriving in California, seeking work. In October, Paul hired Lange to work with him. Together they produced reports that helped to get government projects started.

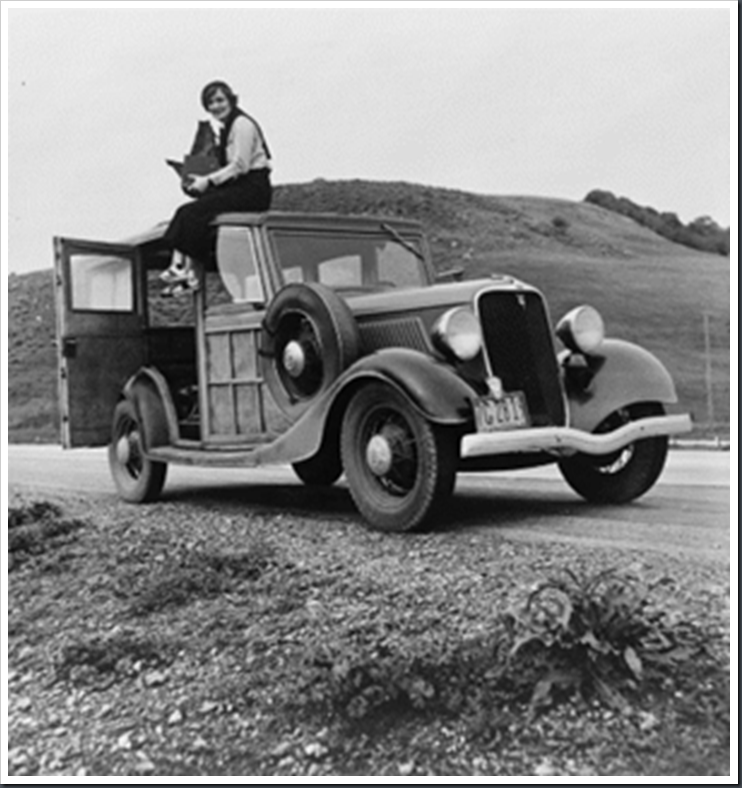

Lange’s reputation was growing and in 1935 she was recruited by Roy Stryker as investigator and field photographer for the federal Resettlement Administration (RA) which later was renamed the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Lange traveled throughout the west, photographing the conditions she saw, often with Taylor working alongside her.

Lange and Dixon;s lives had been moving apart. They filed for a divorce and later in 1935 their divorce was final. Lange and Taylor were married on December 6, 1935. Once again, because Lange and Taylor were so busy, their children were boarded out periodically.

Lange had a unique approach to documentary photography. She saw herself as a documentary photographer and an artist. Her technique was to chat with those she was photographing, sitting with them, listening to what they had to say about their lives. Her handicap that resulted from her childhood bout with polio was an advantage. She gained their trust and put them at ease. She took notes on what they said and used these quotes as the captions on her photographs. She brought a humility to her work which enabled her to create the beautiful, heart-rending, insightful photographs for which she is so well know. She was a pioneer in documentary photography that went far beyond the factual.

“It is not a factual photograph per se. The documentary photograph carries with it another thing, a quality in the subject that the artist responds to. It is a photograph which carries the full meaning of the episode or the circumstance or the situation that can only be revealed – because you can’t really recapture it – by this other quality. There is no real warfare between the artist and the documentary photographer. He has to be both.”

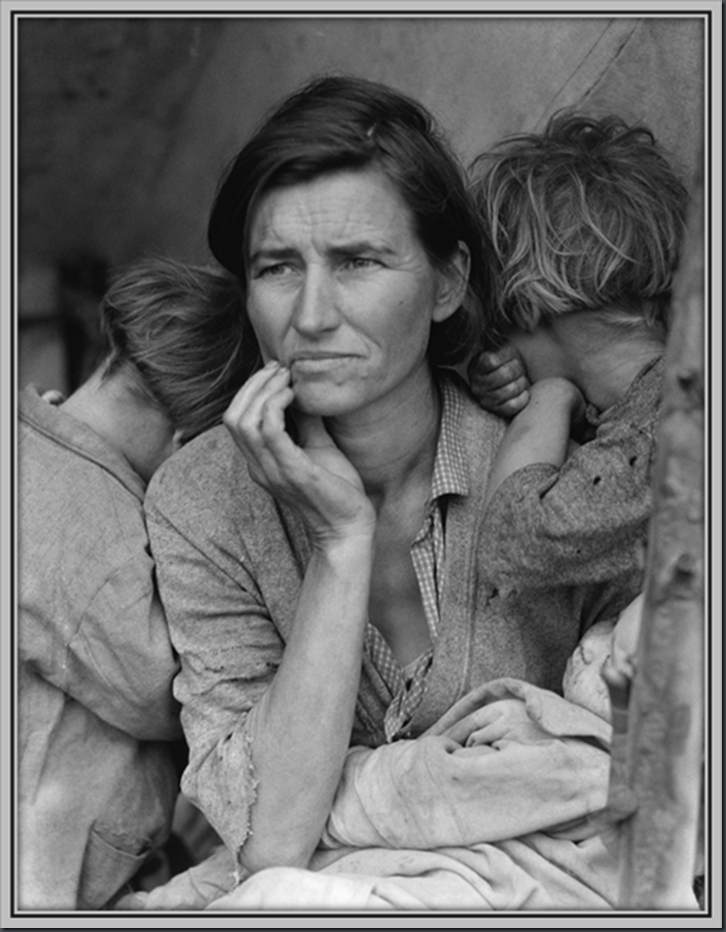

It was in 1936, Lange made the definitive photograph of her career. Originally titled Pea Picker Family, California, it eventually became known as Migrant Mother. It is perhaps the best known and most widely recognized photograph taken during the Great Depression. She was driving through California’s central valley when she saw a sign reading “Pea-Pickers Camp.” She didn’t pay any attention to it and kept on going. But 20 miles down the road she decided she had to see what was going on there, turned around and went back. She met a mother and two of her children and didn’t even bother to ask their names. They started talking and Lange learned they were living off of frozen vegetables from the fields that surrounded them and birds that her children were able to kill.

Lange made this photograph of the three of them. Within a few days it was published in the San Francisco News and shortly after that the U.S. government announced they were sending 20,000 pounds of food to the pea picker’s camp. By the time the food arrived, the mother and her family had moved on. At the time no one knew who she was. It wasn’t until 1978 that Florence Owens Thompson came forward and wrote a letter to the Modesto Bee newspaper, identifying herself as the “Migrant Mother.” When she died in 1983, just after her 80th birthday, President Ronald Reagan offered his condolences, writing “Mrs. Thompson’s passing represents the loss of an American who symbolizes strength and determination in the midst of the Great Depression.”

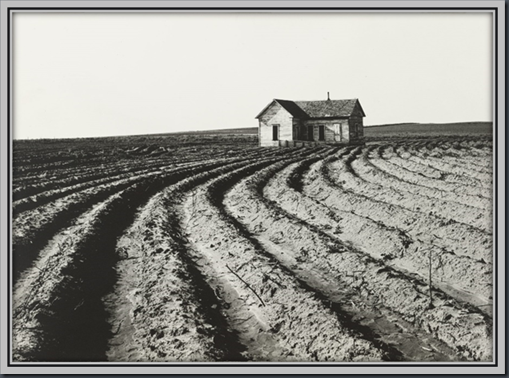

Throughout 1936 and in the following years, Lange and Taylor continued traveling extensively. They were asked by Roy Stryker to do a government project to find jobs for those who had become unemployed in New York City. Next, they traveled through the South photographing tenant farmers and sharecroppers. Lange photographed the in Alabama, Oklahoma and Texas. In 1939 she photographed the effect mechanized agriculture was having on California farmers.

Lange also published extensively. Some were her own work and others were in collaboration with Taylor. For example, on March 1936, two works were published in the San Francisco News under the headline “Ragged, Hungry, Broke, Harvest Workers Live in Squallor [sic]” Followed by an editorial under the title “What Does the ‘New Deal’ Mean To This Mother and Her Children?”. Lange’s Migrant Mother photograph was included.

In 1939, Lange and Taylor published An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion. It was unique in that it used Lange’s photographs and the direct quotes from the migrants themselves. The gathering war in Europe overshadowed the book’s release. However, that does not diminish in any way its powerful presentation of the hardship brought on by the depression and dust bowl.

World War II

On December 7th, 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor resulting in the United States declaring war on Japan. Germany, in solidarity with Japan, in turn declared war on the U.S. Up to that time the U.S. was supplying equipment and supplies to the war effort but now we were officially in the Second World War with boots on the ground.

Meanwhile, Lange was the first woman photographer to be awarded a Guggenheim fellowship “to do a photographic study of the American social scene.” However, she gave it back to go on assignment for the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to document the forced relocation of the Japanese Americans into relocation centers.

Lange photographed the relocation efforts in the west, not only in the large relocation centers but also the temporary assembly centers. Manzanar was the first of what was to be ten major relocation centers and most of her work was done there. She documented the trauma the families when through and the resilience of the Japanese people as they adapted to life in detention.

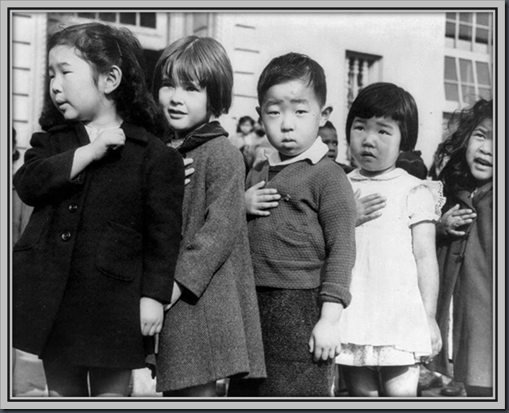

But her sympathies for the oppressed influenced her photographs. This photograph of young children of all races including the Japanese saying the Pledge of Allegiance are particularly moving. Due to the implications of her works, her photographs for the WRA were impounded by the government for the duration of the war.

Today, these photographs are available in the National Archives.

Besides the FSA and the War Relocation Authority, she also worked for the U.S. Bureau of Agriculture Economics, the Office of War and Information and the United Nations.

Her Legacy

In 1945, illness set in that affected Lange for the rest of her life. At the time, medicine hadn’t advanced to the point where it could identify its origin but later it was recognized as a result of her having had polio. It slowed her down but didn’t stop her.

Lange made a number of contributions to various magazines. In 1943-1944, Lange collaborated with Ansel Adams to create a photo essay for Fortune magazine on the war shipyards in Richmond, CA. In 1953, she and Adams along with her son Daniel Dixon collaborated again on a story for Life of three Mormon communities in Utah. In 1954 she and her son completed a story for Life on Ireland and the Irish people. That same year, she assisted Edward Steichen by reviewing the west coast photographs for inclusion in his groundbreaking exhibition, “Family of Man.” By the way, more of Lange’s photographs were included in the exhibition than any other photographer. In 1952 she co-founded Aperture magazine. Also that year, MoMA included 36 of her photographs in an exhibition titled “Diogenes with a Camera.”

In 1955, Lange and Pirkle Jones began work on the “Death of a Valley” project for Life which documented the inundation of the town of Monticello resulting from the creation of the Berryessa reservoir. When the project was completed in 1957, however, Life cancelled the story. Lange later published it in Aperture in 1959.

1958 was another busy year. Nineteen of her photographs were included in a book Beaumont and Nancy Newhall published titled Masters of Photography. She also taught a class at the California School of Fine arts titled, “The Camera, an Instrument of Inward Vision: Where Do I Live?” And she accompanied her husband, who now works for the United Nations and AID, on his travels to Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Burma, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In the 1960s she traveled with Taylor to Ecuador and Venezuela, had a one-person exhibition of her images of rural American women at the Carl Siembab Gallery in Boston. Phil Greene, a videographer and her teaching assistant, began photographing a documentary on her life. More travels with Taylor took them to the University of Alexandria in Egypt where Taylor was a consultant.

Very importantly, John Szarkowski, the legendary curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, proposed a major retrospective of Lange’s works and they began to work on the show. At the same time, she was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus. But work with Szarkowski continued on the retrospective and the two film documentaries created by Greene were produced.

Dorothea Lange died of cancer on October 11, 1965. Her retrospective at MoMA opened January 1966.

Since her death she continues to receive recognition for the her contribution to helping those that were reduced to desperation by the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, ultimately receiving the assistance they needed. And she reminded us of the trauma of the forced resettlement of Japanese Americans during the Second World War. Her humility and humanity merged with her incredible artistic aptitude and gave her the ability to document the human condition that penetrated far beyond the simple facts of the situation to expose so much more.

(328)