Let’s face it, megapixels have been a great marketing tool. “The more there are, all the better,” or so the logic goes. And when a camera manufacturer announces another big jump in megapixels, the photography world sits up takes notice. The question, however, is, ‘How many megapixels do you really need?” Admittedly, this may be different from, “How many megapixels do you want?” The answer to the second question kind of depends on your financial resources and the desire to stay on top of new technology developments. But there is an objective answer to the first question (although it may not be gratifying). But to answer it we need to start at the beginning…

What is a Pixel?

A pixel, or picture element, is a term commonly used across many media – camera sensors, monitors, TVs, etc. But each has its own design. We will stick to the camera sensors.

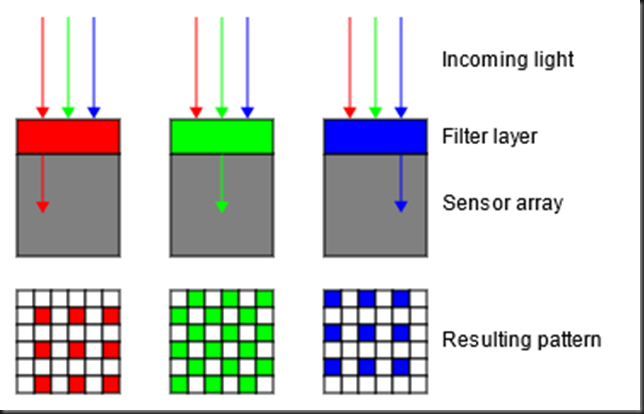

A single pixel is made up of four elements called pixel sensors arranged in a square pattern. And each element has a colored filter – one red, one blue and two green. It’s called the Bayer pattern.

Cambridge in Color has a great article titled Digital Camera Sensors, if you care to take a deeper look. The high-level overview begins with colored light coming through the lens and falling on the sensor. At each pixel element the intensity of red, green or blue light is captured. The intensity is voltages that capture a continuous range of brightness, something like dimming or brightening a light bulb. The computer’s processor, among other things, converts the continuous signal from each element into 32,766 discrete digital steps (14 bits). And that is what gets saved on your memory card as a RAW file.

The important takeaway, however, is that each pixel is made up of four elements – one red, one blue and two green.

By the way, you’re probably asking, “Why two green elements?” Well, as it turns out, that mimics the color sensitivity in our eyes. You see, the cones in our retina are sensitive to red, green and blue light. But it turns out that our eyes are more sensitive to green than red or blue. So, making the sensors with two green elements mirrors what the way our eyes work.

Moving on….

What Is the Relationship between Sensor Size and Megapixels?

Sensors come in different sizes. I don’t think that’s news for anyone. In the DSLR and mirrorless world we generally think in terms of full-frame and crop sensors of which there are several formats. Across all digital cameras, including smart phones, the sensor size varies dramatically as shown below.

Imagine what you must do to the size of each pixel to put 12 million of them in the full-frame sensor shown at the top of the image above verses the 1/2.5” or 1/1.7” sensors at the bottom which, by the way, are the sizes of the sensors in smart phones. If the physical size of a pixel has an impact on image quality (which it does), then full-frame sensors win the quality contest hands down. And, by the way, I chose 12 MP for this comparison because that’s the typical pixel count found in smart phone cameras today.

Does the Pixel Size Matter?

In what way are larger pixels better than smaller ones? Larger pixels gather more light because they have a larger surface area. Even with the same aperture and shutter speed, the larger pixels will gather more light than the smaller ones. The primary advantage is that more light means less noise. And with less noise you get smoother tonal gradation, particularly in the shadow areas.

Admittedly, technology advances in noise reduction have made a huge difference in all pixel sizes, including the smaller ones. But it is still true that larger pixels have lower noise levels than smaller ones.

What about Sensor Size?

Larger sensors can hold more pixels with larger pixel sizes than smaller sensors with the same number of pixels. With more pixels you can get potentially higher image resolutions with the ability to capture more detail. And with larger pixel sizes you get improved image quality. However, the higher resolutions require higher quality lenses to provide the resolution that takes advantage of the larger pixel count.

Unrelated to pixel count, larger sensors can give you a shallower depth of field for more pronounced bokeh effects. This can be a beneficial boost to your creative vision by increasing background blur. Larger sensors also give you a wider angle of view for your lenses.

However, smaller sensors have their own advantages. You get a zoom effect with a smaller sensor. For example, a 50mm lens on a full frame sensor camera has an effective focal length of 75mm on a Nikon APS-C sensor. As a result, crop sensors are better for wildlife photography where long lenses are critical. But as for full-frame sensors, they are better for capturing the grand landscape.

Smaller sensor cameras are often less expensive than their full-frame counterparts and therefore more appealing to many photographers.

In Summary…

- Larger pixels provide higher image quality.

- Larger sensors have larger pixels than smaller sensors of the same pixel count.

- Larger sensors with higher pixel counts have greater image resolution, provided that the lens used has a resolution that matches the sensor resolution.

- Larger sensors take full advantage of wide-angle lenses, making them more suitable for the grand landscape photographs.

- Smaller sensors create a telephoto effect making them more suitable for wildlife photography.

- Higher pixel counts, regardless of sensor size, create larger RAW files, requiring more storage.

How Many Megapixels Do You Need?

Back to the original question; “How many megapixels do you really need?”

Let’s start with typical pixel counts that are available today.

If you really want a lot of megapixels, you can get a medium format digital camera where the pixel counts start at 100 MP for a Hasselblad H6D-100C and top out at 400 MP for a Hasselblad H6D-400c MS. But these cameras range in price from $10,000 to $50,000. Moving on….

Full-frame sensors start at 24.2 MP for the Panasonic Lumix S1 and the Sony Alpha A9. But Sony has rocketed into the lead with their newly announced 61 MP A7R IV and Canon is not far behind with their 50.6 MP EOS 5DS and EOS 5DS R. Nikon biggest is still the 45.4 MP D850.

But who needs a 61 MP sensor? Well, as with everything in photography, the answer is, “That depends.” The real question is…,

“What do you plan to do with your photographs?”

Sharing Images on the Internet and in Emails

To share your images on the internet there are a couple of factors to consider. The first is the resolution of the monitors that the images will be displayed on. The vast majority of monitors display 72 ppi (pixels per inch). A nice sized image is 900 X 600 pixels. That translates to an image that is 12.5 X 8.3” and at 72 ppi, the total number of pixels is 540,000 or 0.54 MP.

In emails a more common image size is 600 X 400 pixels or 8.3 X 5.5”. That amounts to 240,000 pixels or 0.24 MP.

As a result, images that are intended for the internet are beautifully handled by our 12 MP smart phone cameras.

Making Small Prints

In the days of film, a standard print size was 4 X 6 inches. These are the size you got when your film was processed down at the local drug store chain or those 1-hour turn-around places that popped up everywhere. Some of us have boxes and boxes filled with these memories from the past.

What pixel count equivalent is needed to make a 4 X 6” print? For sure, it’s a lot higher than that needed for the internet. For starters, the pixel density is much greater for a print than it is for the internet. A standard pixel density for print is 300 ppi. For a 4X6” print, this works out to be 1200 X 1800 pixels or 2.16 MP.

Likewise, an 8 X 10” print translates to 2400 X 3000 pixels or 7.2 MP.

Both are within the abilities of our 12 MP smart phone cameras to produce good prints. But beyond this quality begins to fall off, not so much because of the pixel count but because the pixels are so small.

Making Prints to Hang on the Wall

Small prints are great to put in a photo album or in a frame to put on the desk or mantle. But images large enough to hang on the wall are much larger.

One standard size that is neither too small nor too big is 16 X 20”. At 300 ppi, this calculates out to be 28.8 MP. However, sophisticated resizing technologies make it possible to enlarge much smaller images. This requires adding pixels to the image which requires very sophisticated calculations such as bicubic interpolation. It is possible to increase a 12MP pixel image to 16 X 24”. The upsized image will look sharp. However, the resolution can never be greater than what was captured in the original 12 MP file. Upsizing an image adds pixels, but it can’t add detail that’s not there.

In the other direction, downsizing an image requires removing pixels. Again, sophisticated calculations such as bicubic interpolation must be performed to accomplish this. To make a 16 X 20” print from a 60 MP sensor, 31.2 MP must be removed to get the image down to 28.8 MP. Removing that much produces a print with the same resolution as a 28.8 MP sensor.

To realize maximum detail in a print from a 60 MP sensor, the print would need to be 29.1 X 19.6” at 300 dpi. Larger prints could be made with the same amount of detail, but smaller prints would lose detail.

What Is Practical

A print that would go over a sofa and be a focal point in a typical living room is typically 24 X 36”. A 20 MP image will have no trouble making a print of that size. In fact, a 20 MP image will easily scale up to 40 X 60”.

Another consideration is the medium the photograph is printed on. The highest resolution is on glossy media such as glossy, luster and metallic papers or metallic and acrylic prints. Non-glossy media have lesser resolutions. This includes matte, watercolor and fine art papers as well as prints on canvas and wood.

What kind of images take advantage of the extremely high resolution of a high MP sensor? Here’s the image that is on the Canon’s website for their 50.6 MP sensor.

This is impressive, even on a monitor. I would like to see it as a 40 X 60” print. But personally, I don’t know when I’ve ever encountered an image with this much detail in landscape photography. More importantly, assuming that such a landscape image could be found, how important would the fine detail be in creating an expressive photograph. Would it be more important than light and composition, the color palette used to create a mood, subtleties in tonal and hue gradation, the emphasis and presentation of the images key elements and the experience the viewer has when viewing the photograph?

When capturing minute detail is needed for making photographs that are moving and expressive, then I’ll need to upgrade. But for now, my landscape photographs do not need more detail than I already have to achieve my creative vision. I’m quite happy with my paltry 30.4 MP.

I invite you to join me in one of my photography workshops.

(1014)