The Pictorialist movement was born among photographers who were primarily scientists. They fervently believed that photography was not limited to faithfully recording the physical world. They saw the camera as more than a mere mechanical device and they were intent on proving it could create art.

It’s not surprising that they turned for guidance to paintings. If a photograph was to be regarded as art, what better way than to make a photograph that looked like a painting. And besides, painters had already worked out the principles and standards for art over centuries. Why try to invent something new when there was such a wealth of knowledge and tradition at one’s disposal.

If one was so inclined, one could mark the beginning of the Pictorialist movement in 1869 when Henry Peach Robinson used the word in his book Pictorial Effects in Photography…, although the tradition had already taken root. This approach of employing well established standards of painting to photographs had a powerful following that lasted for nearly 100 years.

The Influence of Modernism

At the same time, Modernism was beginning to sweep across Europe in the late 19th century. In many ways, Modernism was the antithesis of the Pictorialist movement. Instead of sanctifying tradition, Modernism rejected it in its entirety. It was utter rebellion against the sensibilities of the establishment. Modernism permeated science, mathematics, philosophy, politics, the economy, literature, psychology and painting.

The Modernist movement was triggered by advances of technology. As if out of nowhere, technology was changing people’s lives. Tasks that were tedious and time-consuming became effortless. Technology was ushering in luxury and leisure time that was available to the masses. It promised a utopian way of life.

But it also shattered self-esteem and feelings of self-worth for many. Rather than a person taking pride from creating a product from start to finish, assembly lines reduced an individual’s contribution to one small, insignificant component.

In the realm of painting, the rejection of tradition was so entrenched that even as new, exciting movements were born, they were quickly discarded in favor of even newer movements. There was a rapid succession of isms: secessionism, fauvism, expressionism, cubism, futurism, constructivism, dada, and surrealism. Painters rejected the traditional notion that art had to be a realistic depiction of nature, people and society.

So, it’s not surprising that with all of this going on, Modernism infiltrated photography.

Stieglitz becomes a Straight Photographer

Alfred Stieglitz was committed to the Pictorialist movement. When in 1902 he was asked to put together a photography exhibit for the National Arts Club he ended up in conflict with some of the more conservative members of the club regarding which photographs to include. He resolved the differences by seceding from the club and creating his own private exhibit. He invited other Pictorialist photographers to join him and on February 17, 1902, the Photo-Secessionist group was established.

It is likely that Stieglitz modeled his group after an exhibit in Munich, Germany in 1898 titled the Munich Secession Exhibit. The content of the exhibit was described as,

“In Munich, the art-centre of Germany, the ‘Secessionists’, a body of artists comprising the most advanced and gifted men of their times, who (as the name indicates have broken away from the narrow rules of custom and tradition) have admitted the claims of the pictorial photograph to be judged on its merits as a work of art independently, and without considering the fact that it has been produced through the medium of the camera.”

Stieglitz’s own characterization of the photo-session movement was a “rebellion against the insincere attitude of the unbeliever, of the Philistine, and largely exhibition authorities.” He sure didn’t hesitate to speak his mind. The photo-secession group was dissolved in 1917, largely because members dropped out because of Stieglitz’s autocratic ways.

In a sense, Pictorialism and the Photo-secession movements were in step with the Modernist movement that was creating one of the most exciting periods of innovation in art. Out with the old and in with the new.

But photography was not exempt from the tendency of the Modernist movement to quickly throw out the isms it gave birth to.

As part of the Photo-secession movement, Stieglitz created a publication titled Photo Works. As early as 1904, Sadakichi Hartmann published an article titled A Plea for Straight Photography. In the article, Hartmann made the argument that, “We expect an etching to look like an etching, and a lithograph to look like a lithograph, why then should not a photographic print look like a photographic print?”

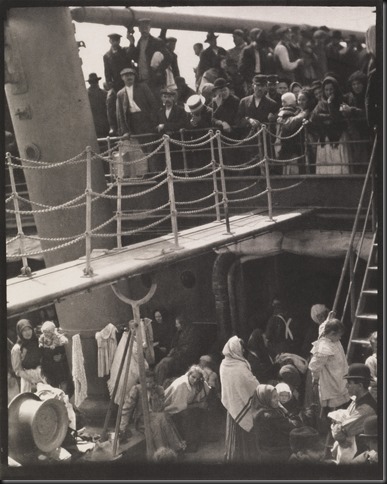

Stieglitz’s best known and most respected photograph, The Steerage taken in June of 1907, came from the first inklings of an emerging new passion. It is regarded as one of the best photographs of all time because of the way it documents its time and as a prime example of modernism photography.

Stieglitz’s best known and most respected photograph, The Steerage taken in June of 1907, came from the first inklings of an emerging new passion. It is regarded as one of the best photographs of all time because of the way it documents its time and as a prime example of modernism photography.

Stieglitz took the photograph while he and his wife were on passage to Europe on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm II. He saw the scene while roaming the ship and went back to his suite to get his camera, a hand-held 4×5 Auto-Graflex that exposed glass plates.

Stieglitz later proclaimed this photograph was “another milestone in photography…a step in my own evolution, a spontaneous discovery, ” However, Stiglitz continued making Pictorialist photographs for several years. It wasn’t until 1911 that he published The Steerage and it was 1913 that it was included in an exhibit. There is speculation that it wasn’t until later that Stieglitz recognized the true impact of this image.

By 1916 Stieglitz was proclaiming is work to be “intensely direct…. Not a trace of hand work on either negative or prints. No diffused focus. Just the straight goods. On [some things] the lens stopped down to 128. But everything simplified in spite of endless detail.” He had departed from the norms of Pictorialism.

The once ardent promoter of Pictorialist photography for the purposes of establishing photography as a legitimate art form now found it abhorrent.

“It is high time that the stupidity and sham in pictorial photography be struck a solarplexus blow… Claims of art won’t do. Let the photographer make a perfect photograph. And if he happens to be a lover of perfection and a seer, the resulting photograph will be straight and beautiful – a true photograph.”

The Modernist movement claimed photography in the imitation of paintings as another victim.

Straight Photography in the West

There is no question that the East Coast was a hotbed of photographic innovation in the United States. Many of the legendary names of early photography all operated in and around the East Coast.

But something was also going on out West. Seattle, Southern California and San Francisco were also hotbeds of photography. The Pictorialist movement certainly left its mark on West Coast photography. Photographers that we don’t think of as Pictorialists started out that way. Among them were Ansel Adams, Imogene Cunningham and Edward Weston to name a few.

The hottest of the hotbeds was San Francisco. There was a counterculture attitude among the photographers there. They saw themselves going against the trend. Some of them having dabbled in Pictorialism rebelled against the soft, manipulated photographs in favor of ‘straight’ or ‘pure’ photography.

Straight photography was not devoid of any sort of manipulation as the name may imply today. Rather, it contradicted the kinds of manipulation that was common in Pictorialist photography that resulted in soft, atmospheric photographs. Straight photography produced photographs that looked like photographs. And perhaps even more importantly, its participants tenaciously asserted their rights to freedom of expression, unconstrained by any formal rules of art.

Perhaps the most famous group of straight photographers in the West was the Group f/64. The name itself was a clear refutation of one of the core tenants of Pictorialist photographs – sharp focus throughout (by virtue of the small lens aperture) with precisely defined detail. The first exhibition of the group was on November 15, 1932 in the de Young Museum in San Francisco and included photographs from Group f/64 members – Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke, Edward Weston, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak and Henry Swift.

They were so militant they even drafter a manifesto that said, in part:

“Group f/64 limits its members and invitational names to those workers who are striving to define photography as an art form by simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods. The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography. Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form. The production of the “Pictorialist,” on the other hand, indicates a devotion to principles of art which are directly related to painting and the graphic arts.”

So Pictorialism is out without question. But they go on to say the following:

“The members of Group f/64 believe that photography, as an art form, must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium, and must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself.”

In other words, photography is an art form that stands apart from all other art forms, be they paintings, etchings or drawings. It stands on its own.

Stieglitz’s initial strategy for getting photography recognized as an art form was to put photographs next to paintings in his gallery and shows to draw attention to the similarities. And the Pictorialist movement produced strong correlations between these two visual arts. It’s as though photography was the offspring of painting and was nurtured by painting in its early days. But now it must venture into the world of art and hold its own.

Modernism’s Influence on Photography

The iconoclastic attitudes of the modernist movement created a fertile environment for experimentation and innovation. The effects of modernism were felt in all areas of Western culture.

In science, Albert Einstein published his Special Theory of Relativity in which he postulated that space, time and movement were relative to the frame of reference and that the only thing that was absolute was the speed of light.

Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung were exploring the world of the subconscious, something that had never been considered before.

Technology resulted in more leisure time which improved the quality of life for many. But it also created the assembly line which led to the minimalization of the workers importance and dignity which in turn led to the formation of labor unions and even to the Russian Revolution which affected much of Europe.

Literature produced the likes of James Joyce, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf and Marcel Proust.

Music produced Claude Debussy, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Alban Berg and Anton Webern.

And painting produced Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Cezanne, Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Edvard Munch, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Wassily Kandinsky just to name a few. You get the picture. All of these artists pushed the limits of paint on canvas. Paintings went from realistic to subjective.

This is when photography really began to define itself in its own terms. This is when photography’s independence from all other forms of visual art was established but more than that. Photographers were able to give themselves license to explore its boundaries, address social issues and assault its limits.

Photography as art had reached maturity.

If you missed previous posts in this series, here are their links:

In the Beginning There Was a Camera but No Film

The First Photographers: 1840 – 1860

Photography’s Struggle to be Recognized as Art – Pictorialism

And join me on one of my workshops.

(2478)