“One does not think during creative work, any more than one thinks when driving a car. But one has a background of years – learning, unlearning, success, failure, dreaming, thinking, experience, all this – then the moment of creation, the focusing of all into the moment. So I can make ‘without thought,’ fifteen carefully considered negatives, one every fifteen minutes, given material with as many possibilities. But there is all the eyes have seen in this life to influence me.” – Edward Weston

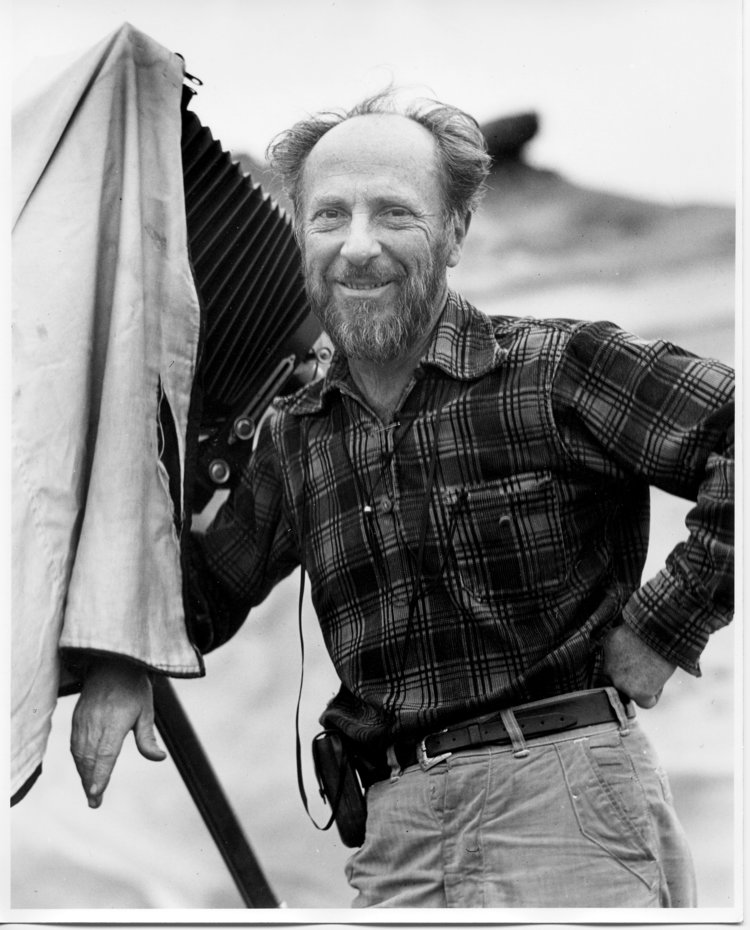

| Note: Not much of Weston’s photographs are in the public domain. Therefore, I have include links to his more important photographs so you can enjoy them. |

Early Life

On March 24, 1886, Edward Henry Weston was born in Highland Park, Illinois into an intellectual family. His father, Edward B. Weston, was an obstetrician and his mother, Alice J. Brett, was a Shakespearean actress. His mother died when he was only five years old and little Edward was raised mostly by his sister Mary who was fourteen years old at the time. Weston called her “May” or “Maisie. They would develop a close relationship which lasted throughout the years.

His father remarried when Weston was nine but neither he nor his sister got along with their stepmother or stepbrother.

When Weston was 11, Mary married and relocated from the Midwest to Southern California, settling in Tropico (later renamed to Glendale). Once Mary left, Weston’s father devoted most of his time to his new wife and her son. He had no interest in books or school and dropped out. He also had a lot of time on his hands and spent it mostly by himself in his room.

In 1902, while on vacation on a farm in Michigan, his father gave him his first camera, a Kodak Bulls-Eye No. 2 for his 16th birthday. His dad included a note which read in part, “you’ll not have to change anything about the Kodak. Always have the sun behind or to the side—never so it shines into the instrument. Don’t be too far from the object you wish to take, or it will be very small. See what you are going to take in the mirror. You can only take twelve pictures, so don’t waste any on things of no interest.”

This not only sparked Weston’s interest but gave direction to his life. Where before he was moody, bashful, restless, and had a bad temper, the camera became like a friend, and he knew then that he would become a photographer. Shortly after receiving the camera from his dad, he purchased a used 5X7 inch view camera. With it he photographed Chicago’s parks and the farm owned by his aunt. He even developed his own negatives and made his own contact prints. Already his photographs revealed what was to follow. Of that time, Weston later reflected, “I feel that my earliest work of 1903 , though immature, is related more closely, both with technique and composition, to my latest work than are several of my photographs dating from 1913 to 1920, a period in which I was trying to be artistic.” The following year one of his works was exhibited in the Art Institute of Chicago. This was the first of many photographs of his that would later be exhibited and published.

1906 was a year where Weston’s emerging abilities as a photographer became more and more recognized. He submitted one of his photographs, Spring Chicago, to the magazine Camera and Darkroom. It was not only accepted for publication in the April issue but was given a full-page spread.

That year, Weston also visited his sister in California. He stayed with her and her family for two months and fell in love with the wide-open terrain. Shortly thereafter, he relocated to Tropico himself and took on various jobs such as a surveyor for San Pedro, California and an itinerant photographer for Salt Lake Railroad. Eventually he went door-to-door, carrying his small postcard camera and offering his services as a photographer for photographing children, pets and funerals. While photography’s center of gravity was on the east coast with the influential Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and the legendary photographers that surrounded them, Weston preferred to stay on the West coast which he did for the rest of his life.

Weston’s Pictorialist Period

It wasn’t long after moving to California that Weston realized he needed professional training in photography if he was serious about becoming a photographer. So, he returned to Effingham, Illinois and enrolled in the Illinois College of Photography. He signed up for their 12-month course and completed it in six months. The school refused to give him his diploma unless he paid the tuition for the full 12-month. Weston declined and returned to California.

Upon his return in 1908, he worked for a couple of studios. The first was George Steckel Portrait Studios in Los Angeles where Weston was employed retouching negatives (a practice that was common in pictorialist photography). But in 1909 he moved to the more established studio of Louis Mojonier whom he stayed with for several years. During this time, he learned the methods of operating a photography studio. Mojonier was particularly impressed with Weston’s abilities with lighting and posing.

Both of these studios produced photographs in the pictorialist style which emulated the Victorian paintings of the day. It was a style that was characterized by soft focus, the selection of typical Victorian themes but perhaps most importantly, a rejection of the sharp realities the camera was most capable of capturing. As a result, the negatives were almost routinely manipulated. Furthermore, Weston’s approach to portraiture was modeled after the paintings of John Singer Sargent, Europe’s leading portrait painter.

Pictorialism was the rage throughout the Western world and Weston had a talent for it. He won many professional awards and achieved financial success. He would continue in this tradition into the early 1920s.

Something else happened in 1909. Weston was introduced to his sister’s best friend, Flora May Chandler. Flora was a grade-school teacher and held a degree from Normal School which later became UCLA. Flora was a distant relative of Harry Chandler who was the head of “the single most powerful family in Southern California”. On January 30, 1909, Weston and Chandler were married. They were to have four sons – Chandler (1910), Brett (1911), Neil (1916) and Cole (1919). Brett and Cole would follow in their father’s footsteps with successful photography careers of their own and the only ones authorized to make prints from their father’s negatives.

In 1911, Weston opened his own studio in Tropico – The Little Studio. He continued producing portraits of the well-to-do customers in the pictorialist style. This is what clients expected in these days, a style he would eventually come to loathe. However, that was not to happen immediately. During these years his reputation grew. His high-key portraits and modern dance studies were popular internationally and articles about him were published in magazines such as American Photography, Photo Era and Photo Magazine.

In 1912, Margrethe Mather moved to Los Angeles and quickly adopted a Bohemian lifestyle including a group of self-styled anarchists made up of actors, artists, and writers. She also joined the Los Angeles Camera Club where she met Weston.

The following year, Mather checked out Weston’s studio and the two of them hit it off. They quickly found that they had the same photographic interests and, within six months after they first met, became intensely involved with each other. Mather’s outgoing, flamboyant and permissive lifestyle was in sharp contrast to Weston’s Midwest upbringing and his wife’s “homely, rigid Puritan, and utterly conventional” personality.

Weston asked Mather to become his studio assistant which she accepted. This marked the beginning of their close, professional and personal relationship that was to last for a decade. Mather persuaded Weston to start a camera club of their own and together, they founded The Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles. The club became influential, but they dropped out after one year.

By 1918, they each had such a profound influence on the other that they frequently shared their thoughts about stylistic ideas and photographic techniques. If one of them ventured into a new realm, the other followed. Their relationship continued to grow and in 1921 Weston made Mather an equal partner in his studio. They even produced a series of a dozen or so prints that they co-signed. They became known as the Art Partners. It was difficult to tell who influenced whom, but Imogen Cunningham confided that when it came to artistic matters, Mather was the teacher and Weston the pupil.

Later Weston described Mather as “the first important person in my life, and perhaps even now, though personal contact has gone, the most important.”

In 1915, Weston started keeping a daily journal which came to be known as his “Daybooks.” In his entries he chronicled his professional triumphs, economic crises, the relationship with his women, his friends and family, his love life and his growth as an artist. He continued making journal entries until 1934. He then burned many of the entries, but others remain and are available in an Aperture publication titled The Daybooks of Edward Weston. It is an inspiring read.

Weston Adopts Modernism

But Weston’s view of photography was changing. As a pictorialist photographer he constantly explored different approaches, stretching its boundaries. But in 1922, he renounced the pictorialist tenants and started producing photographs that were abstract and in sharp focus, emphasizing details.

His sister had moved to Ohio and Weston took that opportunity to visit her. While there, he photographed the abstract shapes of the tall smokestacks of the Armco steel mill. He knew that these photographs were a turning point for him, making images that were abstract, clean-edged instead of soft-focused and sentimental.

From there he continued on to New York where he met Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Georgia O’Keefe and others. Weston characterized his meeting with Stieglitz as challenging and enlivening. He showed them his Armco photographs and they were well received. Stieglitz had this to say about them, “Your work and attitude reassures me. You have shown me at least several prints which have given me a great deal of joy. And I can seldom say that of photographs.” Weston later wrote, “I was ripe to change, was changing, yes changed when I went to New York.”

One of Weston’s comments sheds light on the change he was going through – “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.”

Mexico

In 1921, Weston met Tina Modotti, a young Hollywood actress and political activist who also photographed. An intense romantic and professional relationship quickly sprang up. However, in December of 1921, Modotti moved to Mexico City shortly after her husband Robo de Richey took up residence there, lured by the vibrant art culture and political reforms coming on the heels of the Mexican revolution. It was a Mexican Renaissance in full swing. Shortly after she arrived, however, de Richey died of smallpox.

After her husband’s death Modotti moved back to Los Angeles, but her love of Mexico never died and in 1923 she persuaded Weston to return to Mexico with her. Weston’s oldest son, Chandler, accompanied them. They opened a portrait studio together where they photographed Mexican citizens, artists, writers and revolutionaries. Modotti’s interest in the avant-garde introduced Weston to the creative energy of the time and Weston was able to provide guidance for Modotti and her photography. They worked closely together for the next five years, exchanging ideas and techniques, while each pursed their own unique interests.

Weston was influenced by the simplicity of Mexican art of that day. His photographs from that period emphasized the form of things. Besides the intimate nudes of Modotti, Weston photographed the everyday things around him – household objects, the Mexican flora, arid landscapes, rocks and clouds. One of his most famous photographs from the period was Excusado, a low angle perspective of a toilet.

Weston was also well received by the artist community of Mexico. Such important artists as Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Jose Clemente Orzco encouraged and appreciated Weston’s works, as he did theirs.

In January of 1925, Weston and Chandler returned to California. Weston spent the first few weeks alone in their family home in Glendale, now abandoned and uncared for. In his Daybook he commented how he felt out of place – like a foreigner. In February he traveled north to the Bay Area where life was much more agreeable.

In the middle of June, Weston took the train back to Los Angeles where he had an exhibit at the Japanese Club in August. He was delighted with the results, having received $140 for the photographs that sold. He was pleased that the Japanese had bought his works, commenting that a laundry worker borrowed $52 to purchase a photograph. He complained that he didn’t have this success with white audiences, especially in Los Angeles.

During his time in California, he was accumulating the money he would need to return to Mexico and on August 21, 1925, he and Brett boarded the S. S. Oaxaca, southward bound. Several days later they arrived in Mexico.

Modotti had arranged a joint showing of their work which opened the week he arrived. Once again, they received critical acclaim.

Weston’s photography continued to evolve. He concentrated on folk art, toys and local scenes. He also began a series of heroic portraits, filling the frame with just their faces.

In May 1926, Weston sighed a $1000 contract with author Anita Brenner to make photographs for a book she was writing on Mexican folk art. Weston was obligated to produce three finished prints from 400 8X10 negatives. The three of them, Weston, Modotti and Brett, set out, exploring the lesser-known native arts and crafts. It took until November to complete the work. During that time Weston was able to coach Brett who produced more than two dozen prints that Weston thought were exceptional. But also on that trip, Weston and Modotti grew apart and two weeks after completing his assignment Weston and Brett returned to California for good.

California Here I Come

Upon their return they settled in Glendale. Weston put on an exhibit at the University of California with the works he and Brett created in their last months in Mexico. Weston had 100 images and Brett, who was only 15 at the time, had 20.

In September of 1927, Weston had a major exhibition at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. During the exhibition, Weston met Willard Van Dyke who later introduced him to Ansel Adams.

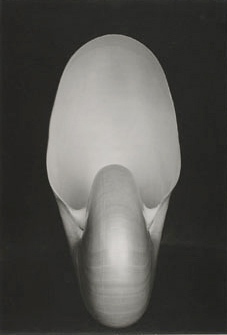

Some of Weston’s most prized and creative photographs came from this period. One influence was Canadian painter Henrietta Shore. Weston was intrigued with her paintings of seashells. He borrowed some from her and in 1927 produced on if his most famous photographs title Nautilus. The simplicity of the title mirrored the simplicity of the design which was groundbreaking for that time. The photograph consisted of the single object, a seashell, and a black background. This gave the shell more than a rendering of its physical self. The isolation and the ambiguous composition opened the physical object to one’s imagination and it becomes much more than a simple shell.

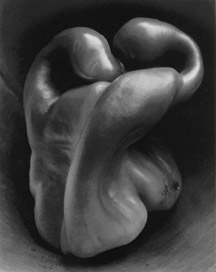

Probably Weston’s most famous photograph and the one used to define him as an artist is Bell Pepper No 30, photographed in 1930. Once again, the bell pepper is isolated from its background, which happened to be a large funnel, but you’d only know that if you were told. And while it is recognizable as a bell pepper, it transcends the literal and takes on other meanings. Weston showed a sense of humor when he said, “…the pepper is beginning to show signs of strain, and tonight should grace a salad. It has been suggested that I am a cannibal to eat my models.”

In works such as these, John Szarkowski, the influential photography curator of the New York Museum of Modern Art said, “The isolation of the subject from any reference to the outside world and the seamless acuity of its description deprives it of scale and context and allows it to operate as a metaphor for the organic unfolding of life itself.”

Weston’s thoughts about landscape photography changed radically over time. In 1922, as he was moveing away from pictorialist photography, he said that straight photography could never photograph landscapes “for the obvious reason that nature unadulterated and unimproved by man – is simply chaos.” But in May of 1928, shortly after returning from Mexico, he and Brett spent a long weekend in the Mojave Desert. He produced twenty-seven photographs and in is journal, proclaimed “these negatives are the most important I have ever made.” He had been inspired by the stark forms and empty spaces he encountered there. When he moved to Carmel in 1929, he started the “Point Lobos Series,” a love that would be constant throughout the rest of his career. He began with closeups of rocks, seaweed and cypress trees but as he continued to evolve, he included broader landscapes and horizons. In 1931, again in his journal he wrote about “an open landscape, or rather a viewpoint that combines my close-up period with distance; a way I have been seeing lately.” His final embrace of landscapes is summed up in this quote. “It seems so utterly naive that landscape – not that of the pictorial school – is not considered of ‘social significance’ when it has a far more important bearing on the human race of a given locale than excrescences called cities.” In less than ten years he had gone from seeing no place at all for landscapes in photography to adopting the genre, with images that ranged from the intimate to the grand.

In April 1929, Weston took up a new mistress, photographer Sonya Noskowiak. She became his model, muse, pupil and assistant. It was Noskowiak that brought him green peppers that ultimately ended up immortalized in Weston’s photographs. They stayed together for five years

With the variety of subjects Weston was photographing, he began to see similarities of form everywhere. “Life is a coherent whole – rocks, clouds, trees, shells, torsos, smokestacks and peppers are interrelated, interdependent parts of that whole.”

In 1932, Weston became one of the founding members of Group f/32 along with Willard Van Dyke, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Sonya Noskowiak, his son Brett and other photographers of the West. The group’s objective was to make photographs based on the capabilities and limitations of the camera in sharp contrast with the pictorialist movement that was still popular at the time. One line from their manifesto sums it up: “Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form.” Three years later the group disbanded but they had made an impact that continues on.

Weston’s influence continued to grow. In 1932, a book was published devoted entirely to Edward Weston’s art – The Art of Edward Weston.”

In 1933, Weston purchased a 4X5 Graflex camera. Prior to that he used his 8X10 view camera. It was big, cumbersome and awkward. The Graflex enabled Weston to be more spontaneous, especially when photographing nudes.

Weston met Charis Wilson while attending a concert. This encounter was in 1934. Of all the mistresses Weston had, Wilson was different. Not only was she beautiful but she had a sparkling personality. Weston wrote this in his Daybook: “A new love came into my life, a most beautiful one, one which will, I believe, stand the test of time.” Weston and Noskowiak were still living together but within two weeks, she was gone. Shortly after, Wilson took her place. It was around this time that Weston ceased making entries in his Daybook with the exception of one last entry written six months later. “After eight months we are closer together than ever. Perhaps C. will be remembered as the great love of my life. Already I have achieved certain heights reached with no other love.”

Guggenheim Fellowship

In 1937 Weston divorced Flora which opened the door for he and Wilson to marry.

In 1936, at the suggestion of Beaumont Newhall, Weston applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship grant. His application consisted of two sentences plus thirty-five of his favorite works. Dorothea Lange and her husband suggested that maybe the application was too brief, so Weston resubmitted it with a four-page letter and a work plan. He didn’t mention that it was written by Wilson.

On March 22, 1937, Weston was awarded a grant of $2000. He was the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship grant. This enabled Weston to buy a new care and he and Wilson traveled through California, Nevada, Arizona, Oregon, New Mexico and Washington, covering 16,687 miles. During the first year, Weston made 1,260 negatives. He also arranged a side deal with the editor of AAA Westways magazine to provide them with 8 to 10 photographs per month for which he received $50. He applied for and received a second Guggenheim grant but instead of traveling, he used the money to print the prior year’s images.

On April 24. 1938, Weston and Wilson were married, and they were able to commission his son Neil to build a small home for them in Carmel on property owned by Wilson’s father. They named it ‘Wildcat Hill’ because of the wave of domestic cats that soon occupied the grounds.

Wilson set up a writing studio in the back of the property and began writing of their experiences traveling for the Guggenheim grant. In 1939 they published Seeing California with Edward Weston. And, with the success of the book, their financial concerns were eased.

Their first book was followed by California and the West the following year. It featured 96 of Weston’s photographs with the text written by Wilson. Also that year, Weston taught a class at the first Ansel Adams Workshop in Yosemite National Park.

Walt Whitman was aware of Weston’s art and invited him to illustrate a new edition of Leaves of Grass. Weston required full creative control which Whitman agreed to. Weston was to receive $1000 for the photographs plus $500 for travel expenses. He and Wilson traveled through 24 states, logging over 20,000 miles. The result was 700 to 800 8X10 negatives. The edition was published. However, the printer took the liberty of tinting the pages green and putting Whitman’s text next to the photographs. Weston was infuriated and considered the project a failure

The Final Years

In 1945, Weston started to show the first symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. He began to withdraw, and Wilson became more interested in local politics and the Carmel cultural scene. They did work on one last project together and published The Cats on Wildcat Hill. But Wilson eventually left him and, since Wildcat Hill was on property owned by Wilson’s father, Weston moved back to Glendale. However, Wilson arranged to sell the proper to Weston and he was able to return.

Weston was honored with a major retrospective at the New York Museum of Modern Art, curated by Nancy and Beaumont Newhall, in celebration of his 60th birthday. The book Edward Weston, edited by Nancy Newhall, was made available as part of the retrospective.

Weston continued photographing but by 1947 needed an assistant to help with his 8X10 camera. As luck would have it, Dody Thompson contacted him, looking for someone to teach her photography. She became his assistant and played a key role in helping him establish his legacy. By the way, Brett and Dody were married in 1952.

Weston took his last photograph in 1948. It was in his beloved Point Lobos and titled “Rocks and Pebbles, 1948.”

In 1950 the Musee National d’Art Moderne in Paris housed a major retrospective. In 1952, his 50th Anniversary Portfolio was published with the prints made by Brett.

He turned his energy to working on printing his legacy. With the help of Cole, Brett and Dody, they produced 8 sets of 8X10 prints from 860 negatives that he considered to be his best work. This project was completed in 1956. Today, the only complete set is housed in the University of California, Santa Cruz.

That same year, the Smithsonian Institute mounted an exhibit of 100 of Weston’s prints titled “The World of Edward Weston.”

Edward Weston died on January 1, 1958, in his home on Wildcat Hill. His sons scattered his ashes in the Pacific Ocean from the beach in Point Lobos known as Pebbly Beach. Today it is named Weston Beach in his honor.

Weston’s Legacy

To summarize Weston’s influence and legacy is something I am not qualified to even attempt. His early training was in pictorialism and he effectively and powerfully, in an attempt to make art, made photographs that emulated paintings. However, when he turned his attention and energies to exploring the capabilities of the camera to produce art based on its own, that is when he did his most powerful and important works

Weston was also a deep thinker and prodigious writer, and the best way to extol his genius is through his own words.

What he tried to accomplish in his photographs

“l do not wish to impose my personality upon nature (any of life’s manifestations), but without prejudice or falsification to become identified with nature, to know things in their very essence, so that what I record is not an interpretation—my idea of what nature should be— but a revelation— a piercing of the smoke screen artificially cast over life by irrelevant, humanly limited exigencies, into an absolute, impersonal recognition.”

What he photographed

“My own eyes are no more than scouts on a preliminary search, for the camera’s eye may entirely change my idea.”

His Way of Working

“I start with no preconceived idea – discovery excites me to focus – then rediscovery through the lens – final form of presentation seen on ground glass, the finished print previsioned completely in every detail of texture, movement, proportion, before exposure – the shutter’s release automatically and finally fixes my conception, allowing no after manipulation – the ultimate end, the print, is but a duplication of all that I saw and felt through my camera.”

“I always work better when I do not reason, when no question of right or wrong enter in, – when my pulse quickens to the form before me without hesitation nor calculation.”

“When subject matter is forced to fit into preconceived patterns, there can be no freshness of vision. Following rules of composition can only lead to a tedious repetition of pictorial cliches.”

Photography as art

“Photography has certain inherent qualities which are only possible with photography – one being the delineation of detail… why limit yourself to what your eyes see when you have such an opportunity to extend your vision?”

Approach to Life

“I feel towards persons as I do towards art, — constructively. Find all the good first. Judge by what has been done, — not by omissions or mistakes. And look well into oneself! A life can well be spent correcting and improving one’s own faults without bothering about others.”

“There is nothing like a Bach fugue to remove me from a discordant moment… only Bach holds up fresh and strong after repeated playing. I can always return to Bach when the other records weary me”

_______________________________________________

I lead photography workshops. Come join me.

(645)