“It is rather amusing, this tendency of the wise to regard a print which has been locally manipulated as irrational photography – this tendency which finds an esthetic tone of expression in the word faked. A MANIPULATED print may be not a photograph. The personal intervention between the action of the light and the print itself may be a blemish on the purity of photography. But, whether this intervention consists merely of marking, shading and tinting in a direct print, or of stippling, painting and scratching on the negative, or of using glycerine, brush and mop on a print, faking has set in, and the results must always depend upon the photographer, upon his personality, his technical ability and his feeling. BUT long before this stage of conscious manipulation has been begun, faking has already set in. In the very beginning, when the operator controls and regulates his time of exposure, when in dark-room the developer is mixed for detail, breadth, flatness or contrast, faking has been resorted to. In fact, every photograph is a fake from start to finish, a purely impersonal, unmanipulated photograph being practically impossible. When all is said, it still remains entirely a matter of degree and ability.” – Edward Steichen

In Luxembourg, a small country wedged between Germany, Belgium and France, is the little known Clervaux Castle secluded in the north of the country. It was built in the 12th century but destroyed in the Battle of the Bulge in the Second World War. Since then it has been restored and now houses the town’s administrative offices and a small museum.

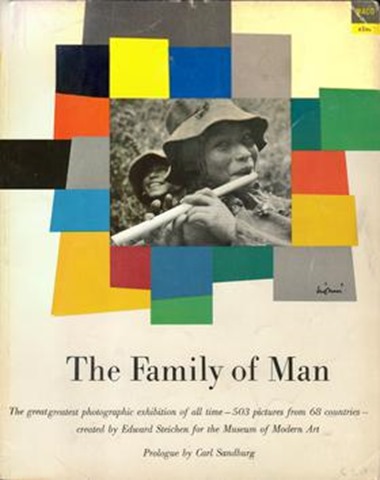

The museum contains an exhibition of over 500 photographs collected from photographers in 36 countries that were assembled and first shown in 1955 at the New York Museum of Modern Art. Since its first showing, the exhibition has traveled around the world and has been seen by more than 9 million people. Finally, it was donated to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and reached its permanent home in the Castle.

Éduard Jean Steichen was born on March 27, 1879 to Jean-Pierre and Marie Kemp Steichen in Bivange, Luxembourg. He was still a toddler when his parents moved to the United States and settled in Hancock located in Michigan’s upper peninsula where his father worked in the copper mines. When his father became incapacitated, they moved to Milwaukee. There his mother supported the family by working as a milliner.

Éduard Jean Steichen was born on March 27, 1879 to Jean-Pierre and Marie Kemp Steichen in Bivange, Luxembourg. He was still a toddler when his parents moved to the United States and settled in Hancock located in Michigan’s upper peninsula where his father worked in the copper mines. When his father became incapacitated, they moved to Milwaukee. There his mother supported the family by working as a milliner.

He attended Pio Nono College, a Catholic boys’ high school when he was 15 and was already showing artistic talent in his drawings. But before finishing high school, he dropped out to become a lithography apprentice at the American Fine Art Company of Milwaukee. He continued drawing and took up painting. In 1895 at the age of 16 he bought his first camera, a secondhand Kodak box “detective” camera. Together with several of his friends who also enjoyed photography, they pooled their money to rent a small room in a Milwaukee office building and formed the Milwaukee Art Students League.

Steichen continued drawing and painting, but he also took to photography for which he obviously had an eye. The first showing of his photographs, at the age of 20, was at the Philadelphia Photographic Salon in 1899. In 1900 Steichen exhibited his photographs in the Chicago Salon. It is there that Clarence H. White, one of the leading proponents of Pictorialist photography and a colleague of the legendary Alfred Stieglitz, saw his photographs and was greatly impressed. He decided he had to introduce Steichen to the Stieglitz in New York, the photographer whose lifelong obsession was to establish photography as a legitimate art and the driving force behind the Pictorialist movement in America. White wrote a letter to Stieglitz, telling him of his find. Stieglitz was interested.

“To make good photographs, to express something, to contribute something to the world he lives in, and to contribute something to the art of photography besides imitations of the best photographers on the market today, that is basic training, the understanding of self.” – Edward Steichen

Later that year, Steichen decided to go to Paris to study painting at Académie Julian in Paris. On the way he made a brief stop in New York to introduce himself to Stieglitz. He brought some of his photographs and Stieglitz was so impressed he bought three of his prints for $5 each. In today’s dollars, that’s about $150. This was the beginning of a close and productive relationship that lasted for many years.

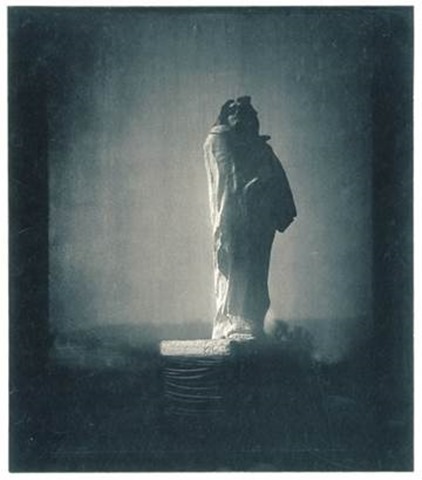

Auguste Rodin was one of the reasons Steichen went to Paris. Rodin had created a large statue of Balzac, the monumental French author. It was so shockingly unconventional that the organization that commissioned it refused to accept it. The scandal that resulted spread across Europe and even made it all the way to Milwaukee. When Steichen saw the image of the statue in the local newspaper, he was immensely impressed. “It was not just the statue of a man; it was the very embodiment of a tribute to genius. It looked like a mountain come to life. It stirred up my interest in going to Paris, where artists of Rodin’s stature lived and worked,” he later wrote.

When he got to Paris, he saw the sculpture where it was exhibited at the Place de l’Alma. But he was too timid to seek out Rodin to introduce himself. So, he studied painting and exhibited his photographs at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. There he met the Norwegian painter, Fritz Thaulow, who introduced Steichen to Rodin who in turn invited Steichen to his Meudon studio where Steichen photographed Rodin at his work for over a year.

It was in Paris, however, that Steichen’s interest in painting began to wane. He became a portrait photographer and honed his skills in two areas – behind the camera and in the darkroom. He also immersed himself in the vibrant art scene, availing himself of the many resources to be found there. In doing so he established himself as a sought-after portraitist of authors, artists and other social celebrities.

“A portrait is not made in the camera but on either side of it.” – Edward Steichen

In 1902, Steichen returned to New York and took up residence in a studio apartment on the fifth floor of an office building at 291 Fifth Avenue to build his portraiture business in which he quickly became highly sought after. A year later he married Clara Smith. Over the course of their marriage they had two daughters, Mary and Kate.

Also, in 1902, Alfred Stieglitz created the Photo-Secession group with the objective to “to advance photography as applied to pictorial expression….” Members were chosen for “meritorious photographic work or labors in behalf of pictorial photography….” Steichen was a founding member.

During this period of Steichen’s career, he produced his most famous photograph from his Pictorialist period – The Pond – Midnight. The image was taken in 1904 in Mamaroneck, New York near the home of his friend and art critic Charles Chaffin.

During this period of Steichen’s career, he produced his most famous photograph from his Pictorialist period – The Pond – Midnight. The image was taken in 1904 in Mamaroneck, New York near the home of his friend and art critic Charles Chaffin.

Today there are three known prints of this image and each is unique because of the printing process Steichen employed. True to Pictorialist sensibilities, the images started as platinum prints. And Steichen enhanced them by hand painting each with gum bichromate which gave them a unique, subtle blue-green hue. This resulted in a photograph that had a tonal richness with a beautiful luminosity.

In February of 2006, the Metropolitan Museum of Art put one of its two prints up for auction at Sotheby’s. It sold for $2,900,000, the highest price paid for a photograph at that time. Some consider The Pond – Midnight as the finest example of Pictorialist photography and certainly one of the most influential photographs ever made.

Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession group needed a place to set up a gallery. Some rooms were available across from Steichen’s studio at 291 Fifth Avenue and, with Steichen’s help, in 1905 The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession became a reality. This small gallery was to quickly gain international recognition. In time the gallery became known simply as 291 from its address on Fifth Avenue.

By 1906, Steichen’s interest in painting was rekindled and he wanted to devote more of his time and energies to that pursuit. He gave up his lucrative portraiture business in New York and moved his family back to France. They settled in Montparnasse, the west bank artist community in Paris.

Steichen and Rodin rekindled their friendship and it was so tight that Rodin was Steichen’s daughter Katherine’s godfather and she her middle name was Rodina.

In an attempt to get more acceptance of the Balzac sculpture, Rodin launched a photographic campaign. He commissioned Steichen to make a photograph. Steichen took a conventional approach by photographing the statue during the day. But Rodin thought there may be value in photographing it at night and Steichen agreed. He spent two nights from dusk to dawn photographing the statue. The negatives turned out well and Steichen experimented with the Pictorialist processes to create what he envisioned. The result was extraordinary.

In an attempt to get more acceptance of the Balzac sculpture, Rodin launched a photographic campaign. He commissioned Steichen to make a photograph. Steichen took a conventional approach by photographing the statue during the day. But Rodin thought there may be value in photographing it at night and Steichen agreed. He spent two nights from dusk to dawn photographing the statue. The negatives turned out well and Steichen experimented with the Pictorialist processes to create what he envisioned. The result was extraordinary.

When Rodin saw it, he was profoundly moved. “It is Christ walking in the wilderness. Your photographs will make the world understand my Balzac.”

Judith Cladel, Rodin’s first biographer, had this to say about the photograph. “On moonlit nights, white and almost phosphorescent, he surged out of the pool of shade covering the ground and stretched his owl-like mask towards the light, like a creature from the world of the occult who has to go back. Rendered visible to profane eyes, he looked like the astral double of the immortal writer. He sent the same shudder through the soul as the ghost of Hamlet’s father when he appeared on the cliff of Elsinore.”

Steichen was active in France besides studying painting and photographic techniques. He helped to create The New Society of American Painters in Paris and exhibited his photographs at the Albright Art Gallery at the International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography in New York. He also fed the works of France’s greatest modernist artists to Stieglitz for exhibition in The Little Galleries, artists such as Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso and more.

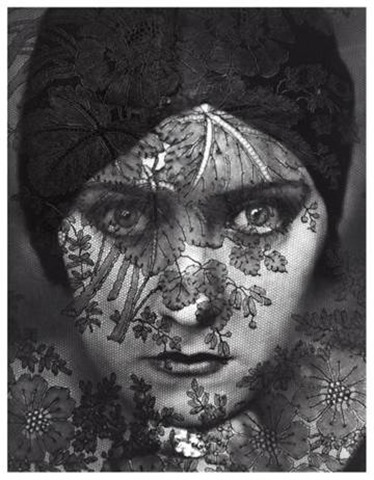

In 1911 Steichen was asked by Lucien Vogel to make his first fashion photograph. The fashion photographers of the day were well established in Europe. But Vogel wanted more. He challenged Steichen to produce a fashion photograph that was art. Steichen applied his Pictorialist skills to the photograph and it was published in the magazine Art et Décoration. The image had a soft focus and was aesthetically enhanced which contrasted sharply with the norm of sharp, detailed photographs. Steichen’s photograph created a mood instead of depicting the physical qualities of the gown. Publishers, designers and marketing people eagerly took to his work.

But the clouds of war were gathering over the European continent. When the First World War broke out on July 28, 1914, Steichen soon returned to New York with his family. He continued painting and photographing. In 1915 he exhibited his paintings at the Knoedler Gallery in New York. It was at this time that Clara returned to France with their two daughters. She accused Steichen of having an affair with Marion H. Beckett. She and her daughters returned to France while Steichen remained in New York. And while the affair was never confirmed, Clara eventually initiated divorce proceedings which was granted in 1922.

In 1917 with the war still raging in Europe, Steichen joined the Army, even though he was beyond the enlistment age cutoff. He was stationed in France where he became commander of the photography division of the Army Expeditionary Forces. Steichen was instrumental in developing a new weapon of war – aerial reconnaissance photography. When Steichen returned to France, Clara returned to the United States with their daughters.

Steichen’s experiences during the war led him to question the extensive manipulations of prints that was the hallmark of the Pictorialist movement. He began to see the possibilities of ‘straight’ photographs, ones that did not require laborious manipulation during the printing process. This began a transition that would continue for several years until he completely abandoned the Pictorialist processes.

In 1919 he resigned his commission in the Army and returned to New York. Clara moved back to Paris.

“When I first became interested in photography, I thought it was the whole cheese. My idea was to have it recognized as one of the fine arts. Today I don’t give a hoot in hell about it. The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself. And that is no mean function.” – Edward Steichen

Upon his return to New York, Steichen pursued his fashion photography with Condé Nast, publisher of  Vogue and Vanity Fair. He also was commissioned by several of the leading advertising agencies. He became the chief photographer at Condé Nast and was paid the astounding annual salary of $35,000. To put that in context, the 2019 equivalent is $500,000. Steichen had moved beyond the Pictorialist processes and photography as art and fully embraced commercial photography.

Vogue and Vanity Fair. He also was commissioned by several of the leading advertising agencies. He became the chief photographer at Condé Nast and was paid the astounding annual salary of $35,000. To put that in context, the 2019 equivalent is $500,000. Steichen had moved beyond the Pictorialist processes and photography as art and fully embraced commercial photography.

The abandonment of photography as art created an irreconcilable schism between Steichen and Stieglitz. The schism started during the war when Steichen supported the allies while Stieglitz, having been born in Germany, was sympathetic to the Germans. But Steichen’s abandonment of fine art photography for commercial fashion photography was far too much of an abomination for Steichen to stomach and their relationship came to an end.

Nevertheless, while Steichen was not using Pictorialist processes anymore, his incredible creativity and imagination turned out some of the greatest fashion photographs ever created.

With Steichen’s divorce from Clara made final in 1922, he married Desboro Glover the following year. Their marriage lasted until Desboro died from leukemia in 1957.

But his time as the most sought-after fashion photographer was ended when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Steichen, now in his 60’s, wanted to contribute to the war effort. He tried to enlist in the Navy but was turned down at first.

But Steichen’s work had already gotten the attention of captain Arthur Radford who was responsible for Naval pilot training and tasked with recruiting 30,000 pilots. He saw how Steichen’s photographs could contribute to his recruitment efforts and invited him to sign on. Steichen said he nearly crawled through the telephone when Radford called him.

In January 1942, Steichen was commissioned lieutenant commander and charged with putting together a group of photographers that would be under his command. His commission and orders – which gave Steichen complete control over his group, where they went and what they photographed – were supported by admiral Chester Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the Pacific fleet. Also in that year, he mounted The Road to Victory exhibition at the New York Museum of Modern Art. Carl Sandburg, his brother-in-law, wrote the descriptions of each photograph.

Steichen selected seven photographers for his photography group. Not surprisingly, they radically broke from the traditional Navy photographer. Steichen directed his men to, “Be sure to bring back some photographs that will satisfy the Navy brass, but spend most of your time making those photographs which you feel should be made. Above all, concentrate on the men. The ships and planes will become obsolete, but the men will always be there.” By the end of his Naval career in 1945, he had attained the rank of captain and was in charge of 4,000 Navy photographers.

Two years after his retirement from the Navy, Steichen was appointed director of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art. It was a controversial appointment as his position in effect demoted the current director and curator, Beaumont Newhall. He was not satisfied with being demoted to curator under the direction of Steichen, a commercial photographer, and promptly resigned along with much of his staff. Many in the field of photography were upset with this move. Ansel Adams expressed his displeasure this way: “To supplant Beaumont Newhall, who has made such a great contribution to the art through his vast knowledge and sympathy for the medium, with a regime which is inevitably favorable to the spectacular and ‘popular’ is indeed a body blow to the progress of creative photography.”

“The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each to himself. And that is the most complicated thing on earth.” – Edward Steichen

Steichen, however, went on to mount more than forty successful exhibits. His most successful exhibit, and the most successful of all time, was The Family of Man which consisted of 503 photographs drawn from 273 photographers from around the world. It ran in New York from January 25 to May 8, 1955. It  then went on tour across the United States and around the world for the next eight years, stopping at thirty-seven countries. Wherever it was shown it drew record-breaking crowds. Steichen said of it, the people “looked at the pictures and the people in the pictures looked back at them. They recognized each other.”

then went on tour across the United States and around the world for the next eight years, stopping at thirty-seven countries. Wherever it was shown it drew record-breaking crowds. Steichen said of it, the people “looked at the pictures and the people in the pictures looked back at them. They recognized each other.”

When the touring days were over the exhibition was donated to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and it now has a permanent home in the Clervaux Castle in Luxembourg.

Steichen finally turned over the director reins at the Museum of Modern Art to John Szarkowski on July 1, 1962.

Shortly before his retirement he married 27-year-old Joanna Taub. Upon his retirement, they left New York city for his farm, Umpawaug, just outside West Redding, Connecticut. There he bred flowers, especially delphiniums. This was not a new undertaking as he had bred them for many years. And of course, he also photographed them.

Steichen published his autobiography in 1962, A Life in Photography. President John F. Kennedy selected Steichen to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom but was assassinated before it could be bestowed. President Linden B. Johnson awarded the medal in 1963. And the Edward Steichen Archive was created at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

Steichen died on his farm on March 25, 1973, two days before his 94th birthday. In 1974 he was posthumously inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

If one was to summarize Edward Steichen’s contribution to photography and art the list is varied and long. He was an artist, expressing himself through painting and Pictorialist photography. He was a successful portrait photographer, both in France and the United States, producing portraits that reflect the innermost cores of his subjects. With his connections to the Modernist artists in France, he helped to introduce Americans to modern art through the 291 Studio. He contributed to the Great War effort by implementing and overseeing aerial photography. After the war he was hugely successfully as a commercial fashion photographer with a keen eye not only for style but also the ability to create compelling photographs for advertisements. This talent enabled him to join the Second World War effort in the Pacific, creating photographs, exhibitions and even a motion picture that promoted the war effort back home. After that war, he became art director and curator for one of the most important museums in the world, the New York Museum of Modern Art. During his tenure he mounted the most successful exhibit of all times, The Family of Man. And finally, in the latter years of his life, he was able to devote himself to an interest that had been on the sidelines for so many years – growing, breeding and photographing delphiniums.

Few photographers have engaged in so many endeavors, all related to photography, nor have they gone through so many significant transformations in their lives as Edward Steichen. His legacy continues lives on.

“Photography is a medium of formidable contradictions. It is both ridiculously easy and almost impossibly difficult. It is easy because its technical rudiments can readily be mastered by anyone with a few simple instructions. It is difficult because, while the artist working in any other medium begins with a blank surface and gradually brings his conception into being, the photographer is the only imagemaker who begins with the picture completed. His emotions, his knowledge, and his native talent are brought into focus and fixed beyond recall the moment the shutter of his camera has closed.”

– Edward Steichen

Ralph Nordstrom leads photography workshops in spectacular locations in the West. Click here for more information.

(563)