“I kept walking the streets, high-strung, and eager to snap scenes of convincing reality, but mainly I wanted to capture the quintessence of the phenomenon in a single image. Photographing, for me, is instant drawing, and the secret is to forget you are carrying a camera. Manufactured or staged photography does not concern me. And if I make a judgement, it can only be on a psychological or sociological level. There are those who take photographs arranged beforehand and those who go out and discover the image and seize it. For me, the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, the master of the instant, which in visual terms, questions and decides simultaneously.”

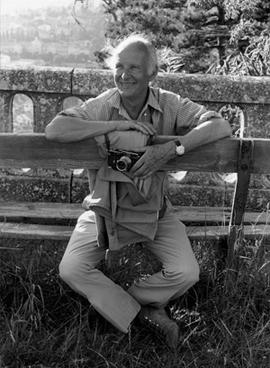

~ Henri Cartier-Bresson

Early Life

On August 22, 1908, Henri Cartier-Bresson was born in Chanteloup-en-Brie, Seine-et-Marne, France. His father was a wealthy textile merchant and his mother’s family were cotton merchants and owned land in Normandy. His father saw him as heir to the family business, but Cartier-Bresson wasn’t interested in being a businessman. After failing the baccalaureate exam three times, at the age of 17, he made is point and received permission to take painting lessons from the French painters Jean Cottenet and Jacques-Émile Blanche.

Cartier-Bresson took to painting but he didn’t take to his parents’ nor his art teacher’s socially conservative leanings. To get away from them, he went abroad to England from 1928 to 1929 to study literature, art, and English at Magdalene College in Cambridge. When he returned to France, he settled in Paris. There he took up with the bohemian crowd and their loose lifestyle and wild parties. He met surrealist painters Salvador Dali and Max Ernst and was fascinated by the juxtaposition of the conscious and the unconscious that was the emphasis of surrealists. He tried to incorporate these principles in his own paintings but was not satisfied with the results and destroyed all his prints. However, his later street photography often reflected the surrealist juxtapositions.

In 1930, Cartier-Bresson was conscripted into the French army and stationed at Le Bourget near Paris. Later he commented on the experience. “I had quite a hard time of it, too, because I was toting [James] Joyce under my arm and a Lebel rifle on my shoulder.” During his tour, Cartier-Bresson was caught hunting without a license and placed under house arrest. Harry Crosby, an American expatriate and nephew of J. P. Morgan, interceded for Cartier-Bresson and persuaded his commandant to keep Henri under his custody. Crosby had an interest in photography and gave Cartier-Bresson his first camera. Together they spent time at Crosby’s home near Paris where they took photographs and printed them. Crosby and Cartier-Bresson had met during their bohemian days in Paris and the sexual permissiveness of those days was still practiced. Cartier-Bresson became involved with Crosby’s wife, Caresse.

Crosby later committed suicide and in 1931 Cartier-Bresson’s relationship with Caresse ended abruptly. He was distraught. During the time he was in the army, he read Out of Africa and decided to travel to French colonial Africa, perhaps to remove himself from his loss. There he supported himself by hunting and selling his kills to the locals.

He eventually grew tired of hunting and, because he had no painting materials, began experimenting with the Brownie camera Crosby had given him. He took pictures of the people he encountered and the unfamiliar world that surrounded him.

All did not go well with him in Africa, however. He contracted blackwater fever (a complication of malaria) and returned to France for treatment. He was so sure he would die that he sent instructions for his funeral to his family. But fortunately for all of us he recovered.

Overall, his experience in Africa prepared him for the photographic career that was about to develop. His hunting expeditions required lightning-fast reactions which would later contribute substantially to his powerful street photography works.

Photographer

In 1932, Cartier-Bresson came across the Leica. It was perfect. It was small and unobtrusive. The small, agile camera enabled him to be spontaneous and take photographs of people in the street without calling attention to himself. And to ensure he remained unobserved, Cartier-Bresson went to far as to paint the chrome on the camera black to further reduce the chance of attracting attention.

By 1933 he had accumulated a portfolio large enough to be exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. Julien Levy, by the way, was someone else Cartier-Bresson met during his wild bohemian days. Later that year, Cartier-Bresson had his second exhibition at the Ateneo Club in Madrid. And the following year he shared an exhibition with Manuel Álvarez Bravo in Mexico. Already his photographs were receiving acclaim and showing the possibilities of street photography.

In 1935, Carmel Snow of Harper’s Bizarre gave him an assignment for a fashion shoot. He had no experience posing models and was not successful. He did not like the idea of posing his subjects and he wasn’t very good at it. He would rather catch them unaware being themselves for which he was incomparable. However, some of his photographs were used in the magazine.

While in New York, Cartier-Bresson met Paul Strand who was doing cinemaphotography at the time. Cartier-Bresson became interested in this medium and upon his return to France took work as an assistant to French filmmaker Jean Renoir. For three years they worked together, producing among other works the critically acclaimed film La Règle Du Jeu (Rules of the Game) in 1939.

Photojournalism

In 1937, Cartier-Bresson undertook his photojournalist assignment when he covered the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth for the French weekly Regards. Instead of photographing the monarchs, he focused on the adoring crowd. He was uncertain about associating himself with these photographs so had them published under the name Cartier. During this time, he also worked for the French communist publication, Ce soir (Tonight), and made his own documentary, Return to Life

Also that year, Cartier-Bresson married a Javanese dancer, Carolina Jeanne de Souza-Ijke. The flat they lived in had a large studio where Cartier-Bresson could do his printing and a tiny bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Cartier-Bresson joined the French Army as a Corporal in the Film and Photo unit. During the Battle of France, he was captured by German forces and spend 35 months in a prisoner-of-war camp where he was compelled to do forced labor. He attempted to escape twice but each time he was caught and returned to camp. The punishment for the attempt was solitary confinement. However, his third attempt was successful. He hid in a farm in Touraine where he finally received false papers that allowed him to travel in France. There he worked for the underground, assisting other escapees, and working with other photographers to document the occupation and ultimate liberation. The American Office of War Information commissioned him to make a documentary about French war prisoners returning from the prisoner-of-war camps. He dug up his beloved Leica that he buried in the farmland near Vosges and proceeded to photograph the war’s aftermath.

This became the center piece of Cartier-Bresson’s first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The Museum thought he was killed during the war and stated that in the exhibit’s brochure, but Cartier-Bresson made a very-much-alive appearance at the show.

In 1947, Magnum was founded. Up until its founding, when photographers were on assignment for a publication, the publication retained the rights to the photographs. The leading photographers of the day banded together to create Magnum which would provide world-class photographers to the publications for assignments. This way the photographers retained the rights to their photographs. Cartier-Bresson was one of the founding members. Through Magnum he was able to concentrate even more on photojournalism when he received assignments in India where he met with Gandhi just days before his assignation and then later covered Gandhi’s funeral in 1948 for Life Magazine which became one of their most prized photo-essays. In 1949 he covered the Chinese Civil War. He continued photographing in the Far East into 1952. His photographs helped to solidify photojournalism as a legitimate art form.

The Decisive Moment

When he returned to Europe in 1952, he published his first book, Images à la Sauvette, or when published in English, The Decisive Moment. The French translation was actually “images on the sly” or “hastily taken images.” Nevertheless, the decisive moment became Cartier-Bresson’s defining legacy. He expressed his work in this way, “To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.”

In 1954, Cartier-Bresson was invited to photograph in the Soviet Union on assignment for Life magazine arranged through Magnum. He continued to take assignments that took him all over the Europe and Asia until he left Magnum ion 1966.

Return to Painting

When Cartier-Bresson left Magnum, he also left photography and returned to the pencil and the brush and canvas. He pursued his first passion of painting and drawing, refusing to even discuss his photography years. He felt that he had already said all he had to say through photography.

Also, at that time he divorced his first wife. Later, in 1970 he married Magnum photographer Martine Frank and in 1972 their daughter was born, Mélanie.

In 1975 he held his first exhibition of drawings at the Carlton Gallery in New York.

He never looked back on his 45 years in photography, saying to NPR’s Susan Stamberg, “I never think about photography. It doesn’t interest me.”

His Legacy

In 2003, Cartier-Bresson along with his wife and daughter and with Belgian photographer and long-time friend Martine Franck created the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris. The purpose of the foundation was to preserve his art.

Henri Cartier-Bresson died on August 3, 2004 in Provence, just a few weeks before his 96th birthday.

Cartier-Bresson was a humanist, preferring to capture ordinary people doing ordinary things. He pioneered the art of street photography and was a genius at capturing the decisive moment.

In his travels all over the world, Cartier-Bresson did not rush. He preferred to move slowly to “live on proper terms” in each country and become totally immersed in the environment. His documentary style can be described as poetic. And while his method of photographing was spontaneous, he repeatedly captured meaning, magic and humor in images that were precisely visually organized.

“You have to forget yourself. You have to be yourself and you have to forget yourself so that the image comes much stronger — what you want by getting involved completely in what you are doing and not thinking. Ideas are very dangerous. You must think all the time, but when you photograph, you aren’t trying to push a point or prove something. You don’t prove anything. It comes by itself.” ~ Henri Cartier-Bresson

Note: Few if any of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs are in the public domain. But you can see them on proprietary websites. One of the best sources is the Magnum website. Here’s the link. Enjoy!

(169)