“I tried to keep both arts alive [concert pianist and landscape photographer], but the camera won. I found that while the camera does not express the soul, perhaps a photograph can!” ~ Ansel Adams

The Early Years

On February 20, 1902, Ansel Easton Adams was the only child born to Charles Hitchcock Adams and Olive Bray Adams in San Francisco, CA. His ancestors immigrated from Ireland in the early 1700s and his grandfather was a wealthy timber baron, a business which his father eventually inherited. It is ironic that Adams detested the timber industry later in life.

At the age of 4 the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 hit. The Adams family house made it through the initial quake unscathed, but Adams’ father thought it best if they sit out the aftershocks outside. A particularly large aftershock caught Adams by surprise, knocking him down. He landed face down against a brick wall and broke his nose. A physician suggested that it would be best to wait until Adams matured to set the broken nose. Later in life, Adams said, “apparently I never matured, as I have yet to see a surgeon about it.”

Adams was a problem child. He was sickly, sometimes spending as much as a month in bed. His Aunt Mary gave him books to occupy his time. One was the Heart of the Sierras which apparently planted an interest in these magnificent mountains in his young mind.

When he started school, he was so rebellious that he got expelled from one school after another. Finally, when Adams was 12, his father faced the inevitable and withdrew him from school for a year. A private tutor was hired so that Adams could continue his education. During his time, he was exposed to the works of the great artists. This lasted for one year before he returned to Mrs. Kate M. Wilkins Private School where he graduated from the 8th grade on June 8, 1917.

During this time Adams started playing the piano. At first, he was self-taught but when he was 12, he started receiving lessons. The discipline of daily practice apparently helped him to gain some control over his disruptive behavior. Adams commented about that time. “The change from a hyperactive Sloppy Joe was not overnight, but was sufficiently abrupt to make some startled people ask, ‘What happened?’ I still recall that the Bach Inventions taxed my concentration, especially when a sunny breeze carrying the sound of the ocean stole through the open window.” As he progressed, his passion for the piano continued to grow so that he planned on becoming a world-class concert pianist.

However, the tide started to change imperceptibly. In 1916 he persuaded his “Uncle Frank” to take him to Yosemite, a destination that he was inspired to see from the books his aunt had given him while he laid ill in bed. And at the same time his father gave him is first camera, an Eastman Kodak Brownie box camera. It was on that trip that he took his first photographs of Yosemite. He later commented, “The splendor of Yosemite burst upon us, and it was glorious. There was light everywhere. A new era began for me.” That was the first of an annual pilgrimage to Yosemite that would continue throughout his life. But he still planned on being a concert pianist.

His interest in photography continued to grow. He started reading photography magazines and attending photography club meetings. In 1917 to 1918 he worked in a photography lab part-time, learning basic darkroom technique.

Adams attempted to mix his music with his annual trip to Yosemite and the Sierra. A park ranger introduced him to a landscape painter, Harry Best who, besides his paining ran a studio in the valley. Best had a piano that he made available to Adams so he could practice while away from home. And wouldn’t you know it – Best also had a beautiful young daughter, Virginia, who caught Adam’s eye. They were married in 1928. Adams began showing his photograph in Best’s studio and when Harry died in 1936, Virginia inherited the studio. Adams continued to display his photographs there. In 1971 the name of the studio changed to the Ansel Adams Gallery and remains that to this day. The family continues to run it.

In 1919, Adams contracted the deadly Spanish Flu and recuperated in Yosemite. That same year he became active in the Sierra Club. For four years, from 1920 to 1923, he was the summer caretaker of the Sierra Club visitor center in the valley, the La Conte Memorial Lodge. He also became a member of the Club’s board of directors in 1934 and served in that capacity for 37 years.

Transition

In the early 1920s, Adams began experimenting with the soft-focus, etching, bromoil process, and other techniques that were hallmarks of the Pictorialist movement. His skills developed and his first photograph was published in 1922 in the Sierra Club Bulletin. But before long, Adams stopped hand coloring his prints, another hallmark of Pictorialist prints although he continued with some of the other practices. It was in 1930 that he met Paul Strand and Georgia O’Keeffe during a two month stay in Taos, New Mexico. Strand was an advocate of straight photography; namely, photographs that featured sharp focus and no manipulation of negatives or prints as practiced by the Pictorialists. Stand shared his techniques with Adams which he immediately adopted.

During this same period, Adams came to realize that his small hands would prevent him from being successful as a concert pianist. And he didn’t like the egos so frequently found on the concert circuit. While he continued to play the piano, he clearly saw his future in photography.

Growing Recognition

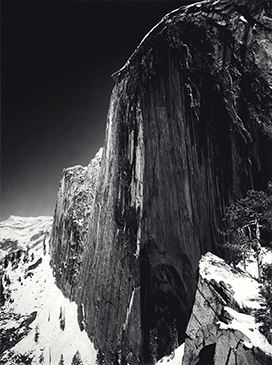

In 1927, Adams made a photograph of Half Dome titled, “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome.” This resulted in “a brooding form, with deep shadows and a distant sharp white peak against a dark sky.” He used a red filter to achieve the effect he envisioned. The result was an image that was almost surreal. The creation of this print was a turning point in his development. It was the first image that he previsualized the final print, a practice that would become his hallmark. He exclaimed that he had finally achieved, “my first conscious visualization” that allowed him to capture “not the way the subject appeared in reality, but how it felt to me”. This photograph was included in the publication that same year of Adams’ first portfolio, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras. It received wide-spread critical acclaim.

In 1931, Adams received a solo exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution, titled “Pictorial Photographs of the Sierra Nevada Mountains by Ansel Adams.” It contained 60 prints of the Sierra Nevada and Canadian mountains. The review in the Washington Post had this to say: “His photographs are like portraits of the giant peaks, which seem to be inhabited by mythical gods.”

In the following year, several things of import occurred. First, Adams participated in a group exhibition with Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston at the M. H. de Young Museum in San Francisco. That same year, these plus several other prominent West Coast photographers formed Group f/64. They advocated sharp focus, the use of the full photographic gray scale from black to white, and the avoidance of any techniques that are taken from other art forms.

n 1933, Adams opened the Ansel Adams Gallery for the Arts in San Francisco and in 1935 he published his first book, Making a Photograph.

In 1936, Adams met Alfred Stieglitz, the legendary promoter of photography as art. Stieglitz was so impressed with the importance of Adams’ work that he mounted only the second one-artist show in his gallery An American Place (the first was Paul Strand 20 years earlier). The show raised criticisms from some critics. Most of the photographers of the day were exposing social and cultural issues, both domestic and international. Adams’ pristine photographs of towering mountains rising about isolated lakes were seen to be sterile and even irrelevant when compared to the displaced farmers during the dust bowl that Dorothea Lange was capturing. Ultimately, however, Adams’ photographs became some of the most powerful arguments for conserving our country’s natural wonders.

Ansel Adams the conservationist continued his activities in successfully lobbying congress to establish Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park. Much of his influence came from the book he published Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail.

His growing fame landed Adams numerous commercial assignments. In fact, he was sought after by companies for the rest of his career. The National Park Service was one of his largest clients, but he was also sought after by Kodak, Fortune magazine, Pacific Gas and Electric Company, AT&T, and the American Trust Company.

The Zone System

In addition to his incomparable aesthetic and expressive eye, Adams was a consummate technician. In 1939 to 1940, Adams in collaboration with Fred Archer perfected the zone system. With it he was able to previsualize the final image, determine the exposure and exactly how the negative would be developed. One of its primary characteristics is that the zone system utilizes the full tonal range of the negatives from which the print was made. Adams published the technique in his book The Negative.

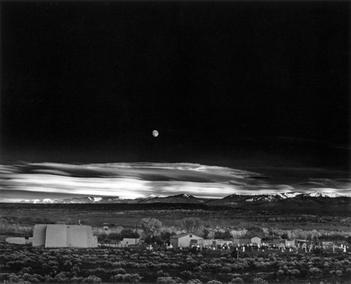

In 1941 the US became involved in the Second World War. Edward Steichen invited Adams to join him as a Navy photographer but Adams wasn’t ready when Steichen needed him, so he was passed by. However, Adams photographed Manzanar, one of the internment camps where the Japanese Americans were taken. His time there resulted in the controversial book Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans. Also, in 1941 Adams was appointed teacher at the Art Center School of Los Angeles. Some of his students were military photographers. But 1941 also had another significant event. His most famous photograph of all, Moonrise over Hernandez, was made that year. It is by far Adams’ most popular work, selling over 1,300 hand printed copies during his career.

In 1946, Adams established the first academic department to teach photography at the California School of Fine Art in San Francisco. That same year he received the first of three Guggenheim grants.

Towards the end of the 1940s, Adams revived the idea of creating portfolios of original photographs that would become artifacts, something to be sold as an art object. His first portfolio of 1948 contained 12 original prints of extraordinary quality and sold for $100. Over the years he produced seven portfolios in all, the last in 1976.

Conservation Movement

In the 1950s Adams published more books. Not only did they depict the art of photography, but he also joined the ranks of those advocating for the preservation of the natural landscape. His most notable conservation publication was This Is the American Earth with commentary by Nancy Newhall published by the Sierra Club in 1960. This joined the ranks of other influential conservation publications like Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac: Sketches Here and There (1949) and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962).

Other major titles include My Camera in the National Parks (1950) and Photographs of the Southwest (1976).

In 1952, Adams was one of the co-founders of Aperture, a magazine devoted to exploring photography as a fine art. Its mission then and now is “to communicate with serious photographers and creative people everywhere, whether professional, amateur or student…”

In 1955, Adams conducted his first of what became his annual photography workshops in Yosemite. They continued to 1981, enlightening thousands of lucky photographers. He continued receiving commercial assignments for another 20 years. He had a monthly retainer with the Polaroid Corporation and took thousands of photographs with Polaroid products.

When Ronald Reagan became president, he appointed James Watt as Secretary of the Interior. Watt initiated policies that were counter to the conservation movement Adams had been advocating. Adams explicitly and forcefully attacked these environmental policies.

Later Career

In the 1960s, Adams’ energetic lifestyle started to catch up with him as he started suffering from gout and arthritis. In an effort to find a more wholesome environment, Ansel and Virginia moved to Carmel Highlands in 1965 where they built their home complete with his darkroom.

It was during this time that photography was more widely recognized as a legitimate art form and galleries began mounting exhibitions of the noted photographers. Adams’ work was frequently displayed around the country.

As time went on, Adams spent more of his time printing his negatives to keep up with the growing demand for his prints and less time photographing nature although he continued to accept commercial commissions.

Adams’ accomplishments continued to be recognized and appreciated as he received more awards. In 1963, Ansel Adams received the Sierra Club John Muir Award. In 1966, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1968, he was awarded the Conservation Service Award by the Department of the Interior. In 1974, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York hosted a retrospective of his works. In 1974, he travelled to France to attend the Rencontres d’Arles festival where, as guest of honor, his works were celebrated. President Jimmy Carter commissioned Adams to make the first official photographic portrait of a U.S. president. And in 1980 President Carter awarded Adams the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Part of the citation read, “It is through [Adams’s] foresight and fortitude that so much of America has been saved for future Americans.” Finally, in 1981, he received the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography.

In addition to all these awards, Adams was intent on giving back when he established the Friends of Photography in San Francisco in 1967 and co-founded the Center for Creative Photography (CCP), one of the world’s finest academic art museums and research facilities for the history of photography at the University of Arizona. It is the home for not only Adams’ works but more than 110,000 works by 2,200 photographers. In their core values they state, “we honor the founding ideals of our institution while responding to the current moment.”

On April 22, 1984, Ansel Adams suffered a heart attack. He was treated at the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula in Monterey, California but died. He was 82 years old and survived by his wife, two children and five grandchildren. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered on Half Dome in Yosemite Valley.

Ansel Adams’ Legacy

Without a doubt, Ansel Adams is the most widely known of all the legendary photographers in this series. His renderings of the wonders of nature and especially the Sierra Nevada Mountains and Yosemite touched the hearts of thousands. His posters were hung on dormitory walls. His books sold thousands of copies and landed on many coffee tables.

This was all part of Adams’ advocacy for conservation and the preservation of our nation’s natural treasures. We owe the incorporation of Kings Canyon into the National Park System to Adams.

Besides his incredible eye that saw more than mountains, lakes, rivers and waterfalls, and his ability to communicate his feelings with us through his photographs, Adams gave us the technology in the Zone System, a process that creates the best possible negative and opens the door to the rest of us to previsualization.

In addition to his books that celebrate nature, Adams made it easy for us as photographers to learn from him with the technical books he published. Perhaps the best book that reveals what was going on in his mind as he previsualized a photograph and the detailed the way he achieved it is ‘Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs.’ Even though his techniques involved view cameras, and black and white film and prints, there is still much we can learn from them, even in the digital age. And in that regard, he still lives on in those of us who study his works and learn from them.

Personal Note: I was leading a group, backpacking in the Yosemite back country. On our third day we arrived at our camping location early. Our plan was to climb Triple Divide Peak. It was an easy class three climb. We arrived at the summit and there we found the registry, a brass cylinder with a screw-on brass cap. We opened it and withdrew the notebook and the stub of a pencil. We flipped through the pages of signatures and filled in the last entries on the last page. Returning to the first page we saw something that surprised us. The register was placed on the summit by the Sierra Club and was signed by the president, John Muir. The club member who placed the registry on the summit was Ansel Adams.

(439)

As a student of photography, he is one of the iconic photographers that can never be duplicated. Many have come close but to me he is the master of black and white photography.