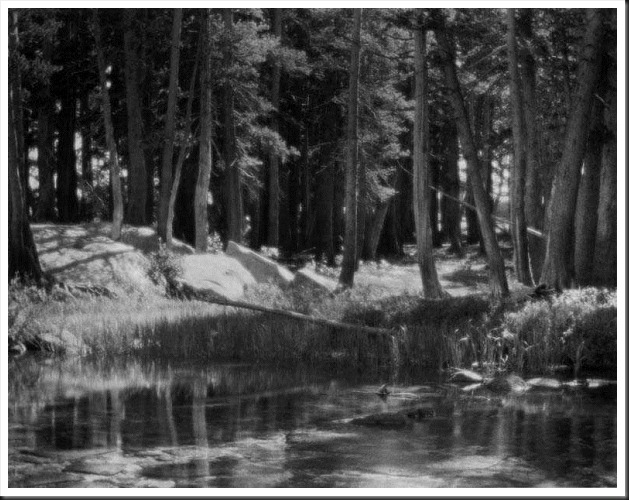

Lodgepole Pines (1921)

This Ansel Adams photograph has always stood out from the rest of his works. It doesn’t have the usual crispness or drama that one normally expects. Instead the focus is soft and the shadows are not full and rich. It almost seems like it might have been created by another person. And for that reason I find it all the more interesting.

It’s difficult to imagine the great Ansel Adams as an amateur, a novice photographer. One normally associates him with a supremely confident master of his art, a pioneer of techniques, both technical and aesthetic, that we still use and revere today. And this is certainly an accurate characterization. But like all of us, he had to start somewhere. We all go through a period where our art is in its formative stages, where we are discovering ourselves, our vision and our voice. And this photograph was part of the process for Adams.

It just so happened that the at that time (early 1920s) photography was not recognized as an art form. Painting was art but photography’s role was mere documentation. Photography was firmly in its Pictorialism period championed by the great Alfred Stieglitz. The generally accepted norm of the time was that for photography to rise to the level of fine art it had to emulate the supreme visual fine art – painting. So photographs were intentionally made to look like paintings, not photographs. A soft quality, a lack of sharp focus and contrast, was especially prized by the Pictorialists. The photography magazines of the day discussed Pictorial techniques, one of which was to use soft focus lenses.

Spring Showers (1902)

Alfred Stieglitz

Adams was an ardent reader of these magazines and eager to try out the techniques they described. So he purchased a soft lens and began exploring its capabilities. Most of his photographs of that period didn’t hold any attraction for him. Except this one. He was fascinated by how the soft lens introduced lens flare and aberrations that imparted a luminance to the photograph, especially in the highlights.

But Pictorialism was not Adams’ bag. It didn’t take long for him to move on. He was of the conviction that photography could stand on its own as fine art, that it didn’t have to imitate painting. He also came to quickly appreciate the beauty in sharply focused images with dramatic contrast. He was one of the founders of the radical group of Western photographers, Group f/64, that rebelled against Stieglitz and the Pictorialist establishment of the East. (By the way, when Adams later showed his Group f/64 work to Stieglitz, he (Stieglitz) recognized it for the great art that it was and immediately committed to a show in New York.)

It’s very interesting to go back in time and realize the struggles photography went through to be able to stand on its own as fine art. It was pioneers like Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham and others so effectively and persuasively made the case.

And the ironic thing is, now that photography is accepted as fine art, many are returning to some of the values of the Pictorialists. But this time around it’s called, Impressionism. And I think that’s a good thing. In my own work I’ve employed techniques and materials to make my photographs look like paintings. No, they’re not soft but at art festivals and shows people often question that they are photographs.

With Lensbaby the soft lens has returned. It offers more creative flexibility then the soft lens Adams employed. And many of todays’ finest photographers like Tony Sweet are creating incredible images with it.

Tony Sweet

William Neill has pioneered a different type of Impressionist photography, the blur. His portfolio, “Impressions of Light,” is supremely beautiful in it’s delicate softness.

William Neill

So we are artists after all. And while there are many commonalities we share with painting we proudly stand on our own. But it took pioneers like Adams and the other Group f/64 members to set photography on the course that has taken it to the place where it is today.

If you enjoyed this post please feel free to share it with your friends or on Facebook. And we’re always interested in hearing from you so don’t hesitate to leave a comment.

We do photography workshops. Come on out and join us. Click here to check us out.

You can also check out our photography. Click here.

WordPress Tags: Ansel,Adams,Photographs,Lodgepole,Pines,drama,Instead,person,novice,photographer,techniques,characterization,vision,photography,role,documentation,Pictorialism,Stieglitz,norm,paintings,Pictorialists,magazines,Pictorial,Showers,reader,capabilities,Most,attraction,Except,aberrations,conviction,Western,photographers,Group,Pictorialist,establishment,East,York,Edward,Weston,Imogen,Cunningham,Impressionism,festivals,Lensbaby,Tony,Sweet,William,Neill,Impressionist,portfolio,Impressions,artists,commonalities,lens,didn

(2946)

This picture was taken with soft focus lens and that is why it lacks the crispness of his most other works. Its not (or not only) because he was an amateur.

Thanks for your comment, Andrzej. Many of the great early photographers adopted the Pictorialist method with the intent to make photographs that looked like paintings. That was their way of claiming photography was art which was hotly contested in those early days. Stieglitz did this, so did Steichen, Cunningham and others including Adams. It was in 1925 that Adams rejected pictorialism and its soft focus, and moved towards ‘straight’ photography which contended that if photography was to be accepted as art, it had to do so on its own strengths and weaknesses and not by imitating other art forms. Adam’s emphasis was on sharpness which later became one of the key parts of the manifesto of the Group f/64. This photograph is one of Adams’ pictorialist images. I wish there were more.

Nice article, Ralph. It’s important to realize artists have a certain trajectory and go through various phases. Later on, after a substantial body of work has been created, you can start seeing clear themes in their work.

Hey Robert, good to hear from you.

Yes, I agree. It’s been over six years that I first started thinking about personal style and I’m just now getting a handle on what mine is. And that was what impressed me about “Lodgepole Pines,” that even the great Ansel Adams went through a period of exploration. I think that’s an exciting period where you’re free to try anything and do. Now my work is more focused or maybe I have a better idea of what I like and don’t like. We grow.

The other aspect of this growth that I’m finding very interesting goes beyond personal style and identifying what you want to say through your art. Art is communication and more and more I’m starting to get a sense of what I want the finished photograph to say at the time I’m pressing the shutter.

It’s all one marvelous journey of self-discovery.