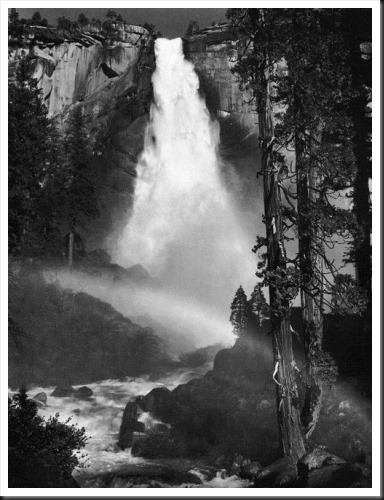

Occasionally at art festivals a visitor to my booth will point to one of my photographs and ask, “Is that what your camera saw?” This question points out a common misunderstanding about the physics and art of photography.

Those of us who are serious about our photography capture our digital images in RAW file format. That’s a format that does a minimal amount of processing on the image before it saves it to the memory card. It is more like what the camera sees.

The other format is JPEG and is not what the camera sees but rather a highly processed image that is controlled to a large extent by the settings the photographer sets in the camera – settings like sharpness, contrast and saturation. So if the photographer likes saturation he just has to up the saturation setting in the camera.

JPEG is much closer to the photographs that were captured in the wonderful days of film. Each different type of file had its own unique way of responding to the scene. Kodachrome film was great for reds while Ektachrome was perfect for blues. Fujichrome was prized for its treatment of greens and its high contrast.

So what did the film camera see? The question is really, “What did the film see?” Was it a faithful documentation of reality? Not in the least. The same can be said for JPEG digital files. They are no more a faithful documentation of reality than film was.

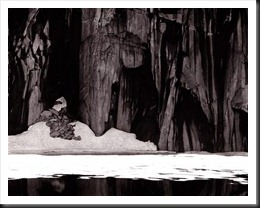

The fact is, RAW files are closer to what the camera saw than film or JPEG files ever were or will be. And, as one workshop participant put it to me, “I don’t like shooting in RAW because the photographs are so plain and uninteresting.” There you go. What the camera sees, exactly what the camera sees, is often plain and uninteresting.

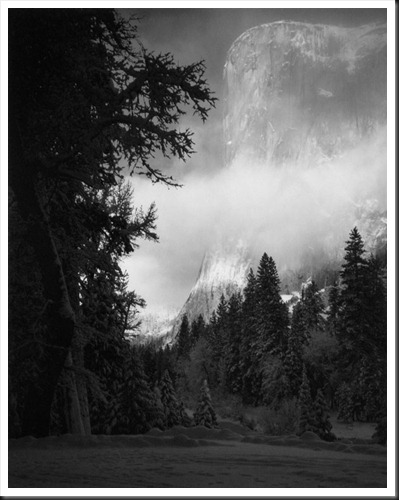

So the physics of digital images captured in RAW format is that the images are the closest to what the camera sees. But from an artistic point of view, these images generally do not speak to us. These are documentation but that’s not art; art is interpretation.

Now, a RAW file is the perfect starting point from which to create art. It is neutral, unbiased and open to the artist to express what she saw, what she experienced that inspired her to set up the camera and compose the image, that led to the decisive moment that the shutter was pressed.

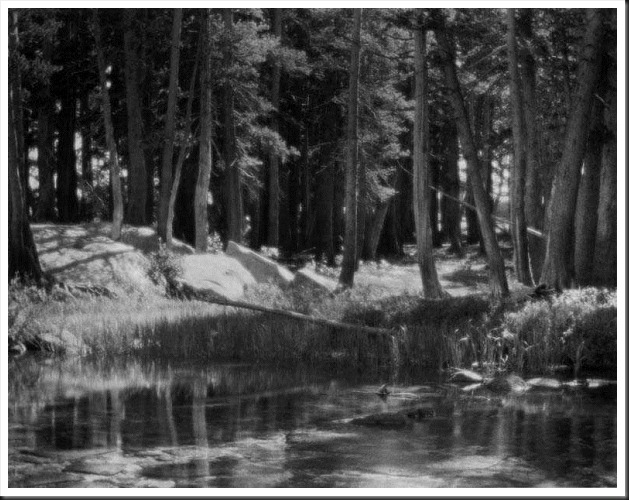

In the days of film we relied on our selection of the type of film that would do the best job of rendering particular situations. In the digital era we have much more powerful tools that we ever had with film – Lightroom, Photoshop, Photomatix and all the wonderful software that we have access to that allows us to express our vision, our interpretation of reality.

So, are my photographs what the camera saw? Not at all. They are what I saw.

We do photography workshops. Come on out and join us. Click here to check us out.

You can also check out our photography. Click here.

(721)